By: Elise Steinberger

It’s another day and the Miss Christy brings in another batch of scientists, students, and new faces. Within minutes of the boat’s arrival, I am introduced to Rohan Sachdeva and Megan Hall, both Ph.D. candidates at USC. They have come to the island for a day trip, to each work on ongoing projects before hopping back on the Miss Christy after lunch.

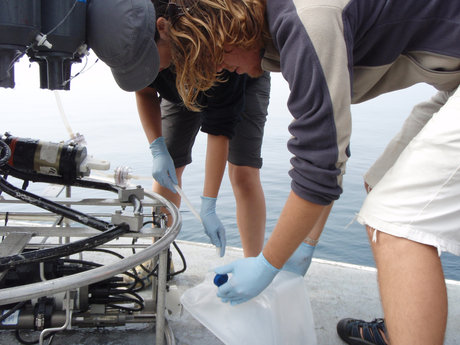

Rohan adjusts his bright white lab coat as describes his marine microbial research. Halfway between Catalina Island and San Pedro, CA, there’s a location where water samples are taken for the San Pedro Ocean Time-series (SPOT). Similar sampling is done around the world, including the Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT) and the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS). For the last ten years, SPOT researchers have collected water from this site once a month at predetermined depths – the deepest being 890 meters. Rohan explains how the sampling bottles are designed with lids that remain open until they reach the desired depth and then are snapped shut before beginning their journey back up to the surface.

Once the water is back in the lab for analysis, scientists examine the microbial composition of the water using sequencing techniques to identify species. Rohan tells me that a teaspoon of water can contain millions of bacteria. By monitoring the microbial composition of the water at different depths and at various times during the year, researchers can better understand how these communities of microbes fluctuate – contributing to our knowledge of ocean cycles, such as those responsible for producing approximately half the O2 available for us to breathe. It’s no surprise, then, that this research could be implicated in studying climate change. As ocean temperature, acidity, and water quality changes, examining the tiny organisms that comprise these microbial communities might help us predict how climate change will affect other organisms and environments linked via these cycles.

The composition of seawater is also of utmost importance to Megan. Her research centers around the effects of dissolved copper on marine organisms – mussels in particular. I help Megan sift through mussels after she pries open a dripping, barnacle-covered cage. As she pulls the mussels out of cage, she explains that the majority of the copper comes from paint that protects the hulls of boats. Megan continues to describe her research as we inspect the shells of dozens of tightly-seal mussels. We discuss California law regarding paint use and Megan’s interest in policy becomes clear. She tells me about the NOAA Sea Grant John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship, a program that places graduate students into 1-year internships with the government in Washington DC to learn about national ocean and coastal policy issues.

Though some might think scientists and researchers only work to solve research questions, but this is not the case. I reflect on Megan’s interest in becoming involved in policy. Having researchers like Megan or Rohan, who are well on their way to becoming experts in their respective fields, apply their knowledge in various political and social spheres would be extremely useful. Because no one person could possibly know the nuances of all scientific fields, Megan’s interest in using her specific knowledge and skill set to advise Marine Policy would be a win-win for everyone. Rather than an ‘Us vs. Them’ mentality, I think this collaborative approach between scientists and politicians is exactly what we need to solve the complex environmental, humanitarian, and public health problems of the twenty-first century.

Elise Steinberger is a fall intern at the Wrigley Marine Science Center, here to learn more about marine science before beginning her Master’s in Health and Science Writing at Northwestern University.