By: Nicole Adams

Besides being adorable, why should we care about the island fox?

The housecat-sized island fox (Urocyon littoralis) lives on six of the eight Channel Islands, and contributes to the flora and fauna found only on the islands. You may have already heard the story of the island foxes, that they suffered great population declines in the last 25 years. Over a span of three years the northern islands’ fox populations declined 96-99% due to hyperpredation by golden eagles. Simultaneously, on the eastern part of Santa Catalina Island there was a 90% population decrease in one year due to a canine distemper virus outbreak.

The island foxes are active during the day (unlike most canids) and can be seen hanging around the picnic tables at the Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies.

Fortunately, rigorous captive breeding programs were swiftly and effectively put in place to save the foxes from sure extinction on some of the islands. Island fox estimates as of 2013 show substantial population growth on the islands that underwent declines. Woohoo! A conservation success story! This is great news for the stability of the channel island ecosystem, but should we declare victory and stop worrying about the foxes?

I don’t think so. The number of foxes has definitely increased, but such severe population decreases can have drastic effects on the genetics of a population. Many questions still remain. How much genetic diversity was lost due to these crashes? What genetic diversity was lost? Which genes were changed as a result? These questions are crucial to answer because genetic diversity allows the foxes to adapt to their ever changing environment.

What does the fox genetics say?

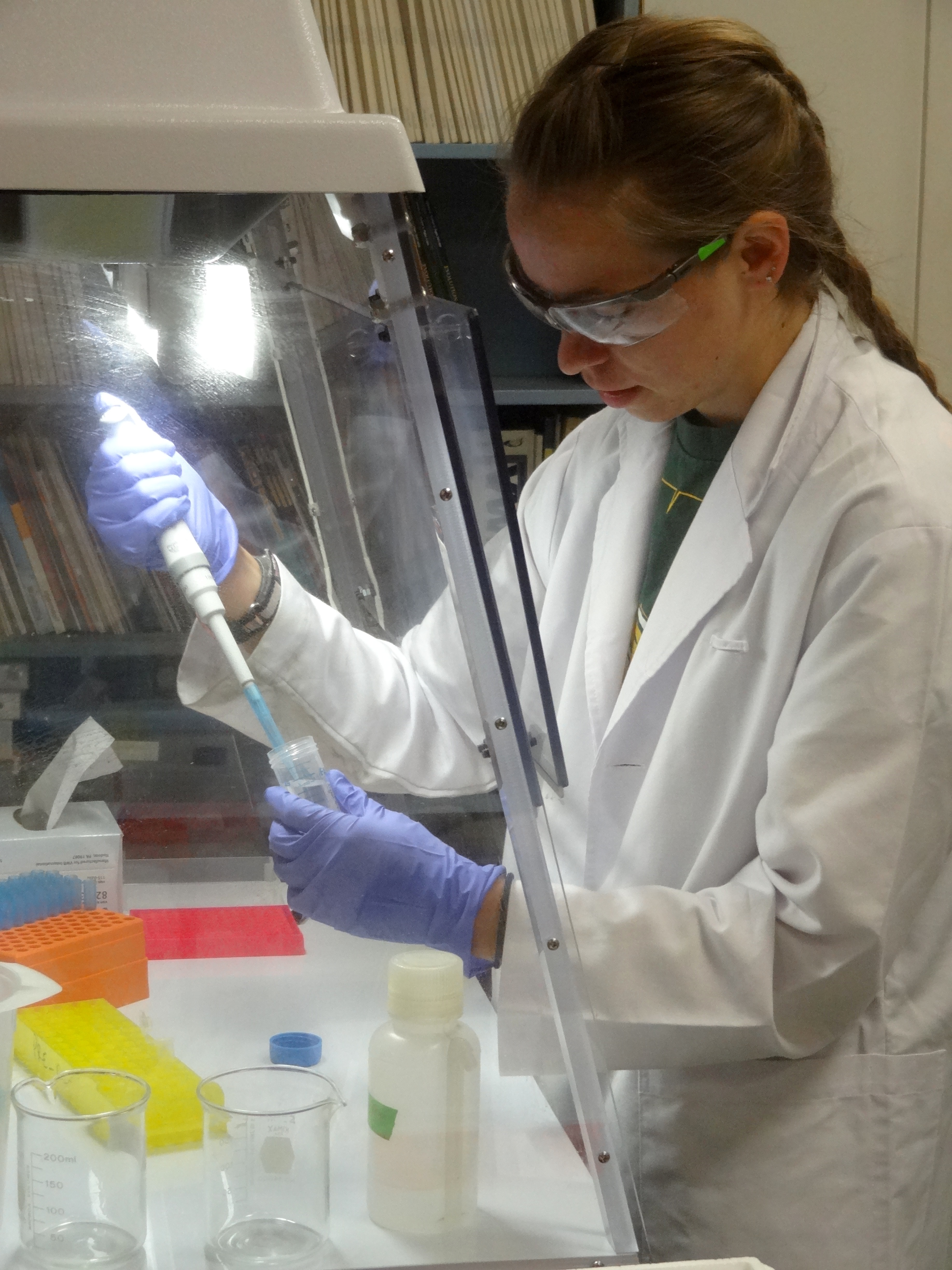

In order to discern the differences in genetics pre- and post- population declines, I am comparing historical museum samples collected prior to the population crashes to samples collected after the crashes. I get to use a really cool and unique collection of island fox skins and skeletons collected in the late 1930s from the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum located just across the street from USC. What I have done is collected “crusties” (the official, scientific term for dried bits of remnant tissue) from the skins and skeletons in order to extract their DNA.

An island fox skull from the LA County Natural History collection, which I get “crusties” from to extract historic DNA.

To compare the genetics pre- and post- population crash, I am also using tissue from foxes collected in the past 10 years. Then the exact code of the pre- and post- decline fox DNA will be determined by sequencing.

What does the fox scat say?

Foxes are continually facing health threats such as from introduced species. Known health concerns in the island fox populations include a number of viruses, bacteria, and fungi that cause diseases. On Catalina, ear mites in the foxes often lead to ear tumors. And a new pathogen, a spiny worm, is currently causing fox fatalities on San Miguel.

It is difficult to know when another outbreak like the one on Santa Catalina Island will occur, what the next pathogen be, or how much genetic diversity will be lost. So it’s important that the fox populations are monitored for the presence of known pathogens and the emergence of new ones. Monitoring for pathogens can be easily done by non-invasive sampling, which attempts to collect useful animal material while causing the least amount of stress on the animal. Therefore, I am monitoring pathogens in fox populations by collecting scat samples, a smelly but non-invasive sampling technique.

I am in the process of getting scat samples from all of the six inhabited islands. I am also working on extracting all available DNA out of the scat sample including that from the fox, bacteria, fungi, and its prey. Then I will sequence common genes that can differentiate among species. Finally, I will compare the sequences from the scat samples to known pathogen sequences and then identify putative pathogens.

The complex population history and the health issues contribute to the need for conservation of the island foxes. I look forward to sharing my results and conclusions and potentially informing the management practice of these curious critters.

Nicole Adams is a Ph.D. student in the lab of Dr. Suzanne Edmands, with the USC Marine and Environmental Biology program. The Edmands group studies evolutionary and population genetics, as well as genetic variation in organisms of concern for conservation and management.

Source: http://assu.stanford.edu/new/pharmacy

http://assu.stanford.edu/new

Very important message to all Internet users. On behalf of our university and the latest research in the field of economy and borrow technologies, we want to warn all the people who are looking for money in debt. So many different proposals for the financial services market today, and many companies are looking for customers with not correct ways. You should strongly beware some sort of search results. Source: http://assu.stanford.edu/new/loansonline

http://ais.ischool.utoronto.ca/loans

http://www.mae.virginia.edu/NewMAE/wp-content.php