The Tao is the Way. In Chinese Buddhism Tao refers to the path to enlightenment, to become one with the Tao through spiritual practice. In anthropology we attempt to become one with the culture of study through participant observation, hanging out with the locals and following their ways. The ideology is to suspend judgment and learn about the culture from the inside out. During the last month I spent some time at two different retreat centers. One was with my anthropology class in Abadiania, Brazil at the Spiritist center of John of God. The other was at the Zen Buddhist monastery, Tassajara, in the hills above Carmel Valley, California. I sat quietly praying and meditating at each center. I attempted to follow the very specific rules about how to dress and how to behave. The rules reflect the discipline of the center as well as efforts to build community and a way to organize the variety of visitors. As one Zen teacher said, “We wake up [at 5:20 a.m. with the bells], we know what to put on, and where to go [to temple].” The rigor of the rules “makes us look sane [she laughs].”

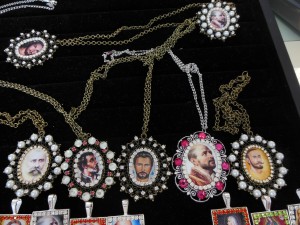

Tim Perille (from USC) wearing a Casa triangle shown with a Portuguese visitor wearing the Spirits jewelry. She creates the necklaces and shares the profit with John of God. Both wear the required white clothes.

At the Casa de Dom Inacio in Abadiania, Brazil visitors are instructed to wear white. We are not only a community but it is said that the Spirits can read your auras better. White is a color of spiritual purity and sanitation as well as the Western biomedical uniform (the white coat). To match the white dress there is a growing trend to accompany this with spiritual jewelry. The Casa gift shop sells beads, crystals, and triangles on necklaces to match the prayer triangles in and around the Casa that say faith, love and charity. There are also necklaces with images of some of the spirits that incarnate through the medium, John of God. Lastly, for this short blog, there are very specific rules of behavior. In the crowded meditation halls, the staff walk the aisles and remind visitors not to cross their arms or legs. Even a bag across the shoulders or a sweater tied around the neck may block the energy of the individual and the room. John of God is said to feel pain if during meditation arms are crossed or eyes peek open. We sit in chairs or wooden benches listening to the Ave Maria played through a sound system or recite the “Our Father” after the silence.

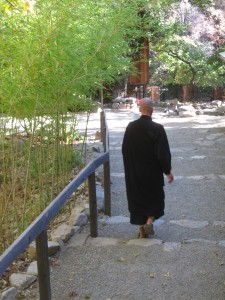

The contrast was startling for me when I wandered into Tassajara two weeks after returning from Brazil. This was to be my five-day vacation, chanting with the monks and working in the famous Tassajara kitchen. (They publish vegetarian cookbooks). In Tassajara visitors are encouraged to wear dark colors while in the Zendo meditation hall. Black is the preferred color. I asked if this affected the spirits or the Buddha. “No,” Sherry at the front desk told me, “we don’t believe anything like that, but it is less distracting.” There are also specific instructions against wearing jewelry. Sherry explained that people even ask if it is acceptable to wear a wedding band inside the temple. “Yes,” she explained, “that is not jewelry, it is a vow.” Again the idea is to not distract. The rules in the Zendo are quite specific: enter the room with the foot closest to the door hinge, bow, find your assigned seat, bow to the seat, bow to the room, and then take your seat cross-legged on the meditation pillow. Palms cross, resting on each other suspended below the navel, thumbs lightly touch. Incense, gongs, and ritual chants in Japanese fill the air. Eyes should remain open, cast down.

As an anthropologist I am fascinated with rituals, the intricate details and their origins. How could these two retreat centers offer such contrasting recommendations? What does it all mean? As the Zen teacher hinted: structure is comforting to the human species, the spirits probably don’t care.

Article and all photos by Dr. Erin Moore, Associate Professor (Teaching), USC Anthropology.