I had actually heard of Jean multiple times before I met him. I suppose his unusual lifestyle had made him somewhat of a celebrity on the Camino.

“There’s a man here – I forget his name – he lives entirely out of a backpack,” an Englishman had informed me, “and he has for 15 years. I admire the courage. Wouldn’t recommend it though.”

“The man’s crazy,” another pilgrim concluded, “he sold everything he ever had. Zero security.”

Mindy (left) and Jean on the trail.

In my mind, he was like some kind of mystic legend, traveling around the world, alone and uninhibited. He didn’t need anyone or any sort of structure. Nothing could tie him down. So it was funny that when I was finally face to face with the gray-haired man in his seventies, with a small frame and a wide smile, I didn’t even realize who he was.

He approached me casually, teasing about the ribbons on the backs of my shoes, “So then is it your job to sweep up the Camino path and keep it clean? Or are those symbolic?”

“Neither,” I laughed, “they’re actually just labels, so they don’t get mixed up with the others”

Author’s shoes (left). The green and polka dot bows keep shoes from being confused with other shoes in the racks outside dorms.

“Ah,” he said, “Smart girl”. He turned to the woman behind him and laughed. She smiled at me.

“Hi I’m Michelle. And this is Jean.” Michelle was tall with blonde curly hair and kind eyes. She looked young for her age, probably in her fifties. She was the mother of three grown children.

“I’m Mindy. Nice to meet you.” I shook both their hands, “Where are you two from? Did you come together?”

“I was born in Quebec,” Jean responded, “and Michelle here is from Indianapolis. And no, we met at the airport in Paris.”

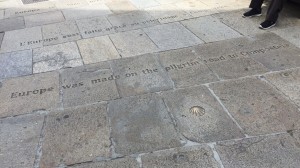

I spent the next 6 hours with the two of them, learning that Jean had traveled to an impressive 40 countries after selling a successful company and all his property. I also listened to Michelle’s retelling of the messy divorce from which she was hoping to heal. This day of the Camino was the famous trek to the Cruz de Ferro, an iron cross where pilgrims traditionally bring and leave a rock from home, a symbol of leaving our burdens behind.

Cruz de Ferro, where pilgrims leave their troubles (and stones) behind.

Michelle left her rock, she stood and stared at the cross somberly. Jean however didn’t leave anything. I asked him about this later.

“Well as you know the rock is supposed to be from home,” he answered.

“What do you mean?”

“Well,” he said cautiously, looking over his shoulder to Michelle who had now fallen so behind she was out of sight.” Sometimes in your life you meet a woman like that. And it changes everything. I thought I wasn’t looking to settle down. Now I want to spend my life with her.” I watched as he picked up heart- shaped rocks and placed them in the middle of our path, telling me he was hoping she’d see them.

Suddenly Jean, the man who couldn’t be tied down, changed drastically before my eyes. He started rambling about how they met, how compatible they were, how he was entranced by her after 15 minutes. It was fate that he found her again on the road, he assured me. They had been walking together for 10 days now.

I do not know what became of Michelle and Jean. But no matter his answer, Jean will always stand out in my memory as the man who embodies the conflicting human needs for freedom and for structure. He had a wanderlust that prompted him to give up everything, going to an extreme that I could never imagine for myself. No stability, no support from family or friends for 15 years. He expressed being tired of routine and social constraints in a way I’ve heard so many describe before him. But he pushed it to an extreme that was unprecedented. He was at once relatable and inconceivable. A paradox.

But even Jean eventually wanted to go back to some sense of structure, of settling down, allowing routine back into his unpredictable life.

“I guess even I can’t wander forever,” he admitted to me as we continued to walk. “I’ve been on a pilgrimage for so many years. I think I’m finally ready for it to end.”