USC Wrigley Institute – wrigley.usc.edu

By Carie Frantz and Victoria Petryshyn

As instructors for the 2014 International Geobiology Course, we sit here at the end of the program wholly exhausted and a bit dizzy after what can only be described as a most excellent summer. We recently said goodbye to the 15 graduate students, and a good dozen other faculty and their families, who had become our summer family during the five week adventure that was this year’s program. It was a happy end to a summer full of fun and excellent science, but it’s always sad to see everyone leave.

Our fabulous students!

The Geobiology Course, which has run at the Wrigley Institute since 2002, trains graduate student scientists from all over the world in the field of Geobiology. This discipline studies the interactions of life (mostly microorganisms) with rock: how biology and the Earth’s surface have co-evolved and influenced one another. Since it spans biology and geology (with a whole lot of the other sciences thrown in), it is interdisciplinary by definition and pushes everyone out of their comfort zone to learn new concepts and techniques. It’s fun. And exhausting.

The course itself officially started June 8th when the students arrived at USC in Los Angeles for orientation, with lectures including “Biology for Geologists”, “Geology for Biologists”, and finally “Dinner for Sausage-ologists”. But really, it started much earlier; the course directors, instructors, and administrators had been preparing for almost a year: plotting themes, scouting field sites, finding speakers, writing protocols, ordering equipment, booking motel rooms… You name it, it had to be thought carefully through and organized.

After orientation, three vans packed with students and instructors drove up to the Eastern Sierra where we spent the better part of a week in the field: at Walker Lake (Nevada), Mono Lake, the Bristlecone Pine Forest, various geological outcrops in the deserts around the Nevada/California border, and at a hot spring near Mammoth. Fun places for sure, but we were all business—filling the vans with bags of rock samples, hundreds of chemistry samples in little glass vials, a large cooler full of microbial mats on ice, and several dozen lab notebooks full of detailed descriptions, measurements, and notes. And of course our tired, sweaty, hungry, but happy students.

Collecting samples (very carefully!) from Little Hot Creek near Mammoth

After our field adventures, we headed to Cal State University at Fullerton, where we spent two weeks in labs analyzing our samples. The students did everything from DNA extraction and amplification to rock cutting and polishing; from genetic sequencing and bioinformatics to high-resolution geochemistry; from microscopy on our biological samples to petrography (=microscopy) on our rock samples.

Oh, and the lectures. Almost every night there were lectures on a range of topics. Lectures were given by the full-time instructors, by visiting scientists, by previous GeoBio students, and even by the current students. The students were a tough crowd–smart, curious, well-versed in a range of fields, and willing to call things into question at the raise of a hand. It’s an environment where the instructors learn as much as the students. Keeps us on our toes.

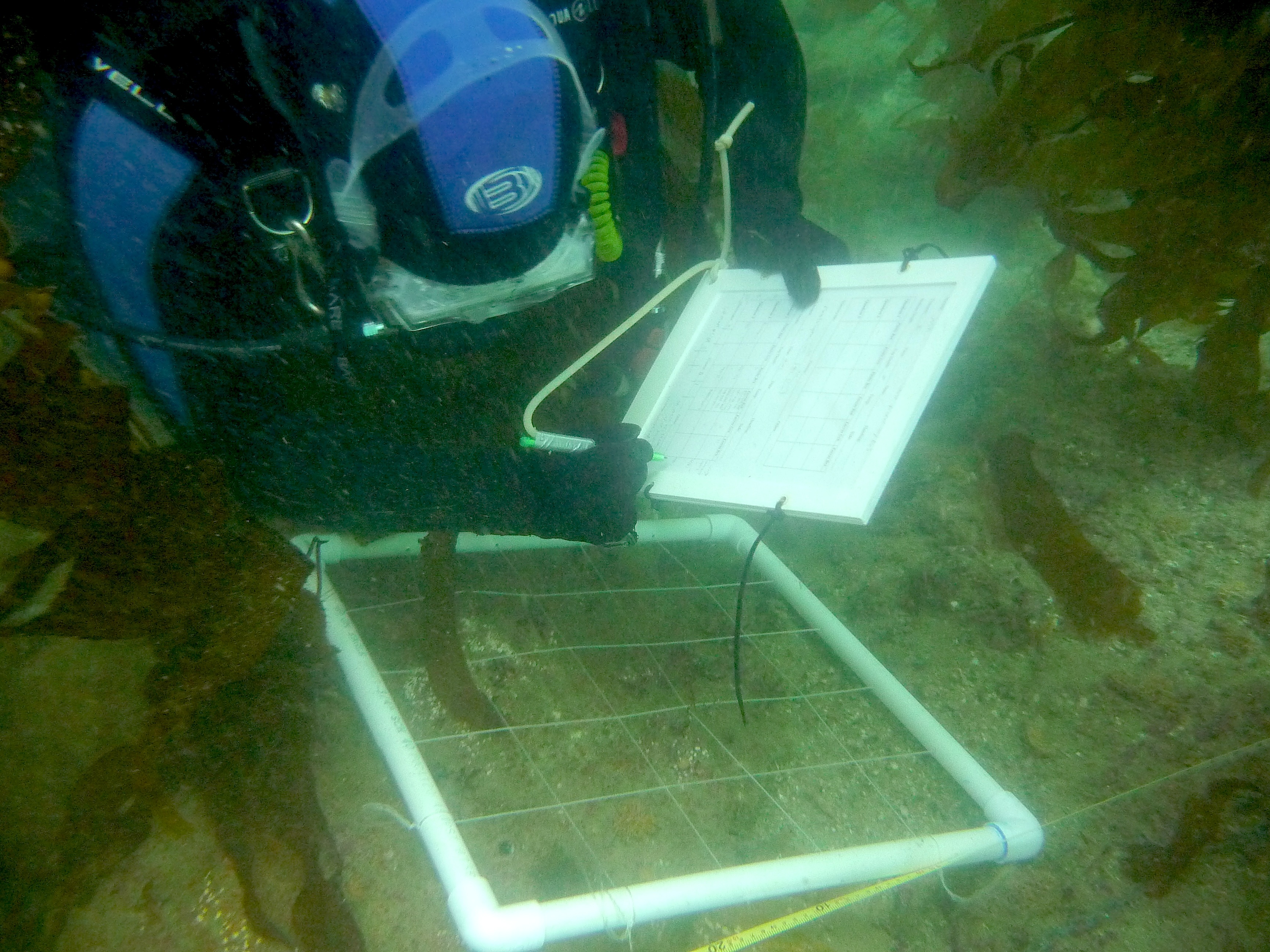

Carie and student Marisol Juarez working with microelectrodes to measure in situ microbial activities at WMSC

After our time at Fullerton, we hopped aboard the WIES Miss Christi boat and headed to Catalina Island, to spend the final two weeks working on group research projects that developed out of the previous fieldwork—real research investigating real unknowns. One group used metagenomics to understand the dramatic environmental changes recorded by 30,000 year-old rocks from our site at Walker Lake. Another group used similar techniques to understand how the microbial mats we collected at the Mammoth hot spring formed carbonate rocks. A third did a chemical and biological profile of the hot spring to understand the controls on the spring’s chemistry. The fourth group sussed out the origin of “hardgrounds” forming at the shore of Walker Lake, and discovered that they were not formed biologically as is often assumed.

The learning continues! Looking for microbial mats in the mud in Cat Harbor

“Island Time” took on unique meaning as the group spent long hours in the WIES labs doing experiments. But we also made time for fun—it’s all about balance, right? Every morning, a group of die-hard students explored the island by kayak. Volleyball tournaments were a nearly daily occurrence. Impromptu dance parties and karaoke nights helped all of us blow off steam. The theme song for this year’s course would have to be “Everything Is Awesome” (although “What does the Fox Say” was a close second, for obvious reasons known to all who have spent time with Catalina’s island foxes).

When we watched the students give their final presentations, we were all impressed by the excellent science that had been done in such a short time and very proud of these biologists-, geologists-, chemists- and engineers-turned-geobiologists. Many of the projects will be presented in the coming months at scientific meetings like the Geological Society of America, the American Geophysical Union, and the American Society for Microbiology. Maybe some will result in published papers. Not bad for a bunch of neophytes after just a few weeks of work!

GeoBiology Class of 2014

Welcome to the Geobiology Family, Class of 2014. Now, get caught up on some sleep, write those conference abstracts, and Keep Being Awesome!

Back to WIES Blog home page