By: Kenny Bolster

At this point, my summer research as a Wrigley Fellow has basically wrapped up. I’ve been off the island for the past couple of weeks because I was presenting my research at the Goldschmidt conference, an international meeting of geochemists that was held in Paris this year. I told them about a new method for measuring a particular chemical form of iron, and then talked about how I’d used that method in Big Fisherman’s Cove at Catalina.

Basically, I’ve been able to show that when you have direct sunlight hitting dust particles in the water, it can cause individual atoms of iron to break free and float off as a dissolved compound, which could then be assimilated by algae or other marine organisms. This process probably matters a lot farther offshore, where organisms are starved for iron and the only source of iron is dust particles that would rapidly sink otherwise.

Quartz flasks of seawater exposed to direct sunlight let me test hypotheses about how mineral particles break down.

Now that the classes have started again, I can’t spend as much time on Catalina as I would like. I’m still going out to do some work, including experiments like the one above, where I’m exposing seawater treated in different ways to sunlight and trying to figure out exactly how particles break down. I’ll also be out there for some work with Yubin Raut, another Wrigley Fellow who’s trying to study how rotting macroalgae affects the chemistry of the water around them.

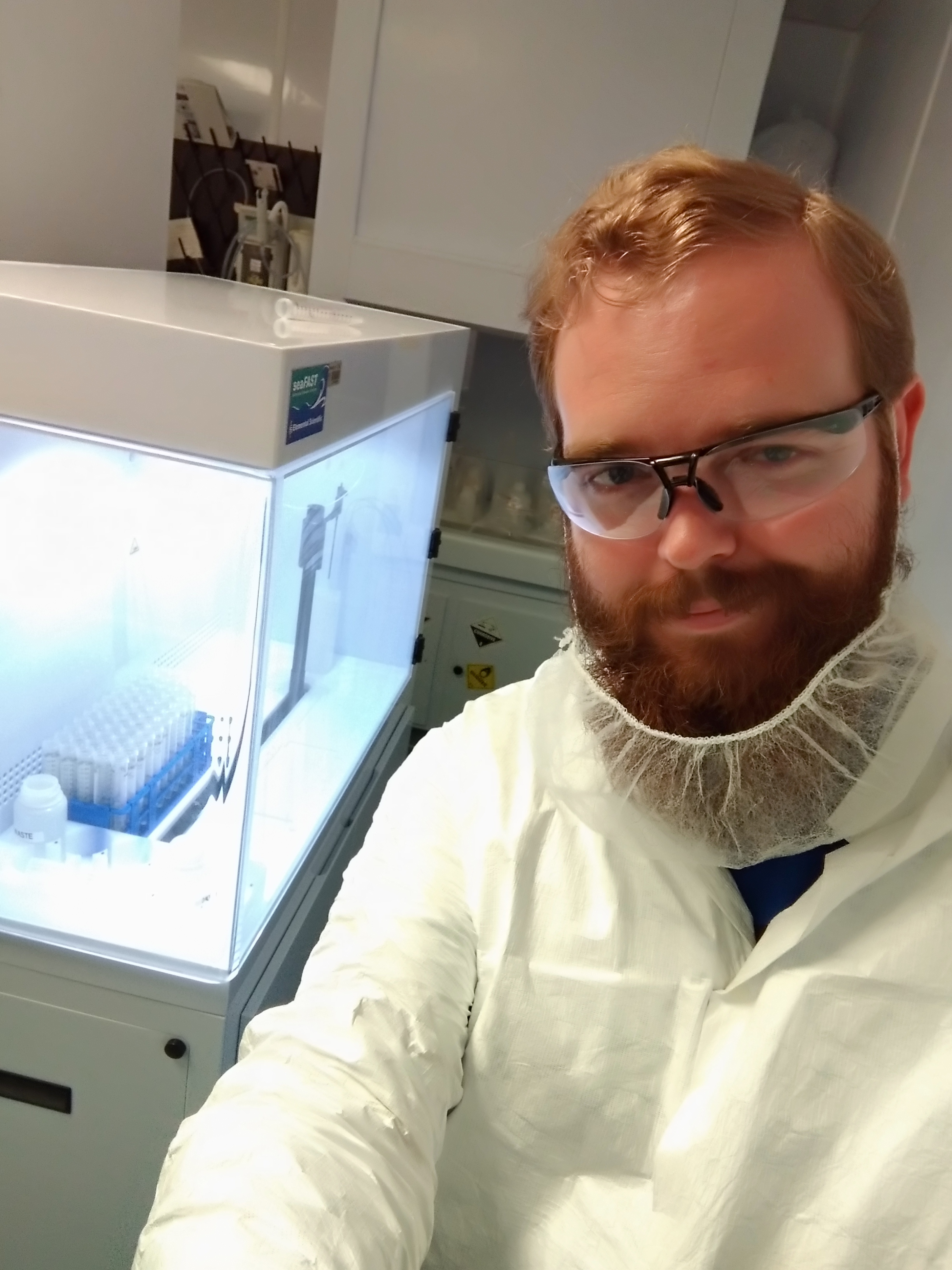

Me, in front of an ESI seaFAST automated preconcentration system. The beard cover is to reduce the chances of getting hair in a sample.

Instead, most of what I’m doing these days is lab work. Over the past summer, I’ve collected a whole bunch of samples of seawater, as well as particles, and now I need to measure the iron concentrations of them. So when I’m not on the island, and not in a class, I’m running those samples through the device in the picture above, which will concentrate the iron in a sample.

The vials that come out of the seaFAST then get put into an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (below). The ICP-MS works by putting the sample into a plasma torch (something non-scientists would call a lightsaber) and then measuring the individual atoms as they go flying off. It’s a very powerful instrument, but like most high-end scientific equipment, it’s finicky enough that we frequently have to open it up and make repairs. That, plus a little bit more lab work on the island, is going to be plenty to keep me busy this fall.