By: Kelley Voss

Hi! My name is Kelley, and I am beginning my fifth year studying octopuses as a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Santa Cruz. This is my second year as a Fellow, and it has looked VERY different from last year. In 2019, my REU student summer mentee, Nikita Sridhar, and I spent five weeks together collecting California two-spot octopuses (Octopus bimaculatus) and watching how they defended themselves from their local predators, the California moray eel (Gymnothorax mordax). Why? We currently have no published research about how octopuses retaliate when they’re attacked by a predator: we know how they could fight (e.g. inking, jetting, hiding, grabbing, biting…), and we know they really commonly lose their arms, but scientists have never quantified how octopuses lose arms to predators in the course of fighting them off. This is where my work comes in: I observe the interactions between the California two-spot octopus and a moray to discover how octopuses may be using, and risking, their arms in self-defense.

Niki (left) and Kelley (right) release a two-spotted octopus at 4th of July Cove

I had planned to have a similar routine as last year: start the day with a nice morning dive to collect octopuses, bring them back to the Wrigley waterfront, and let the octopus hang out in a mesh cube in a tank with an octopus-approved snack for about a day, and conduct behavioral trials in the evening. For each trial, we simply put an octopus into a tank with a moray and allow them to interact freely for an hour, at which time we separate them. We record all trials from two different angles, from above and the side, so we can confidently determine which arms the octopus used to distract or fight back against the moray. We record details about any injuries, especially the location of the arm on the body that was attacked.

A screenshot of a trial video of a California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculatus) about to be attacked by a California moray (Gymnothorax mordax). The octopus kept its arm and survived the encounter!

When I’m not in the water or conducting trials for this project, I analyze the video we recorded to collect behavioral data– the first rule of octopus fight club is, “record EVERYTHING.” This is where my summer virtual intern, Nathalie Benshmuel, came in this year. Last summer, Niki recorded all the octopus behaviors, and this summer, Nathalie recorded all the moray behaviors! This will make it much easier for me to quantify which of the octopus behaviors is a clear retaliation to a predatory attack. Over ten weeks, Nathalie and I met up on Zoom several times a week to discuss what she saw in the videos, put together her proposal and results, and chat about research and grad school. Nathalie found evidence that morays were more aggressive toward female octopuses, which makes me so curious to put the pieces of this arm loss mystery together! About two out of every three octopuses I find in the Two Harbors area has at least one arm that has been lost and is in some stage of regrowth. However, we really don’t know anything about the causes or effects of this very common occurrence. I will use this study as part of my effort to answer bigger questions about how octopuses use their many arms, and how the loss of these arms may affect both themselves and their ecological communities.

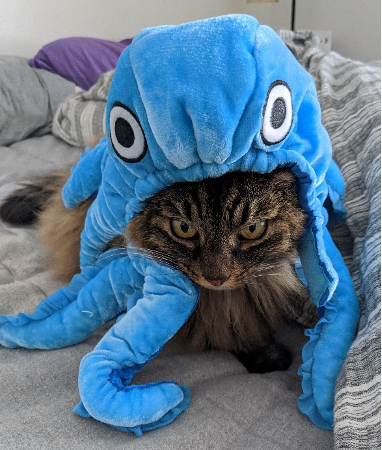

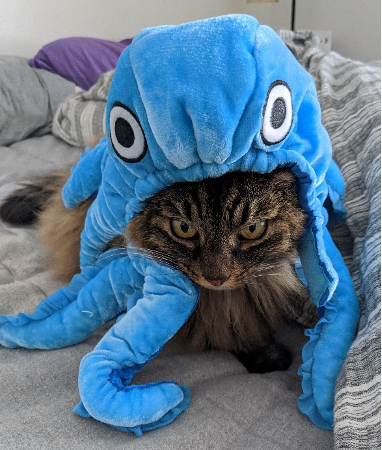

Soft is the only “octopus” Kelley worked with this summer due to the pandemic. She heard the octopuses get shrimp treats, but she refused to get in a tank, so she was excluded from the trial.

So, thanks to COVID-19, I spent my entire 2020 Wrigley Fellowship at home in Santa Cruz, but I still got to intern the wonderful Nathalie and learn so much more about morays in the process! If you want to read more about my work in greater detail, I gave a talk to the Wrigley virtual summer interns that you can find here, or you can visit my website to learn about my other projects: www.kelleyvoss.com.

I would like to thank Nathalie and Niki; my advisor, Dr. Rita Mehta; and everyone who has helped my research happen so far. I am looking forward to getting back to the island and finishing up this project someday soon!