By: Elizabeth Burns

Hi, my name is Elizabeth and I’m very happy to be back at Wrigley! I am a Master’s Student from California State University, Northridge and this is my third year as a Summer Wrigley Fellow at Catalina Island.

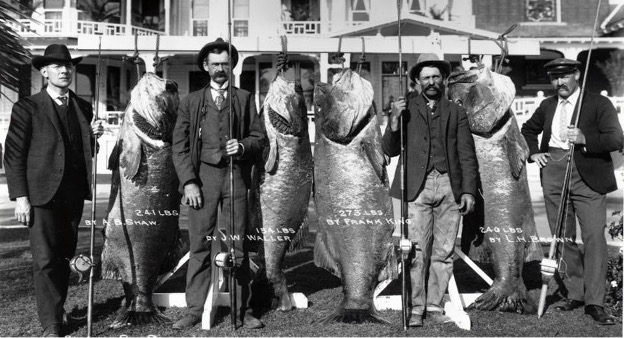

I have the pleasure of researching Giant Sea Bass courtship behaviors and sound production during their spawning. If you’ve never heard of Giant Sea Bass, you wouldn’t be the first. The Giant Sea Bass is the apex predator of the California kelp forest. Research has shown that these fish can live over 76 years of age, grow over 800 pounds, and can reach lengths over 7 feet. (You can check out this video I made on size differences of adult and juvenile Giant Sea Bass.)

Unfortunately, we know very little about these fish due to the severe overfishing they experienced since the early 1900’s. Giant Sea Bass are still feeling the effects of this bottleneck and are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN’s red list.

Due to increasing efforts and protections over the years, Giant Sea Bass populations are slowly on the rise, making it easier to study them. This has allowed us to uncover some of the secrets these giants still hide. We know that a substantial population of Giants congregate every summer at Santa Catalina Island to spawn. But little is known about what actually happens in Giants’ spawning aggregations.

My research focuses on two of the biggest mysteries of the Giant Sea Bass: their courtship behaviors, and sound production during spawning. These are behaviors that have not been properly described or documented before. I hypothesize that they produce sounds and perform other courtship behaviors during such spawning events. Understanding these behaviors and how Giant Sea Bass reproduce are crucial to helping conserve the species.

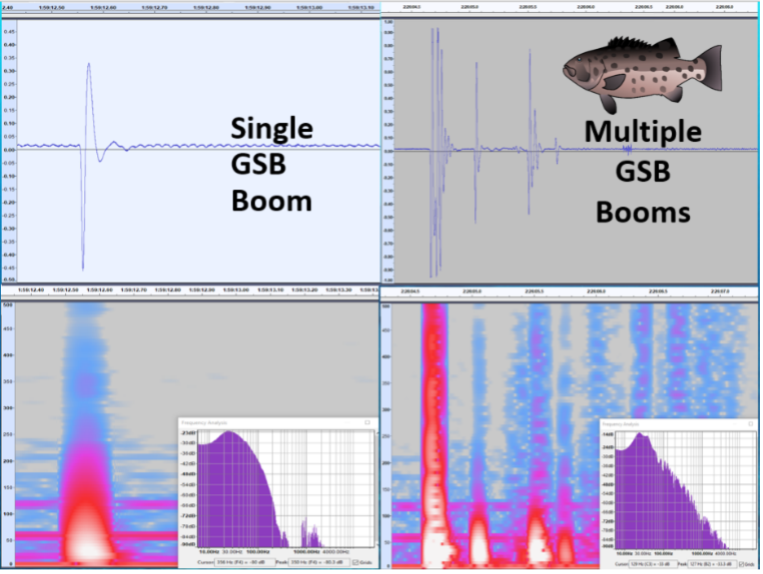

Divers that have the pleasure of swimming with Giant Sea Bass will sometimes get to hear the sounds they make. We think Giants make 2 different sounds to communicate with each other. There is a sort of standard “Boom” to alert other fishes and organisms to their presence, and a “snare drum” like sound for reproduction to entice the ladies. Giants start their courtship behavior at sunset and continue into the early morning. Not only do we believe that male Giants make sounds for their ladies during courtship, but that they also dance with them.

Left: Video of a miscellaneous sound recorded by hydrophone sampling for Giant Sea Bass sounds by Elizabeth Burns. Right: Four images of Giant Sea Bass sounds identified. Top images are wave forms of Giant’s booms and below are the spectrogram of the waveforms.

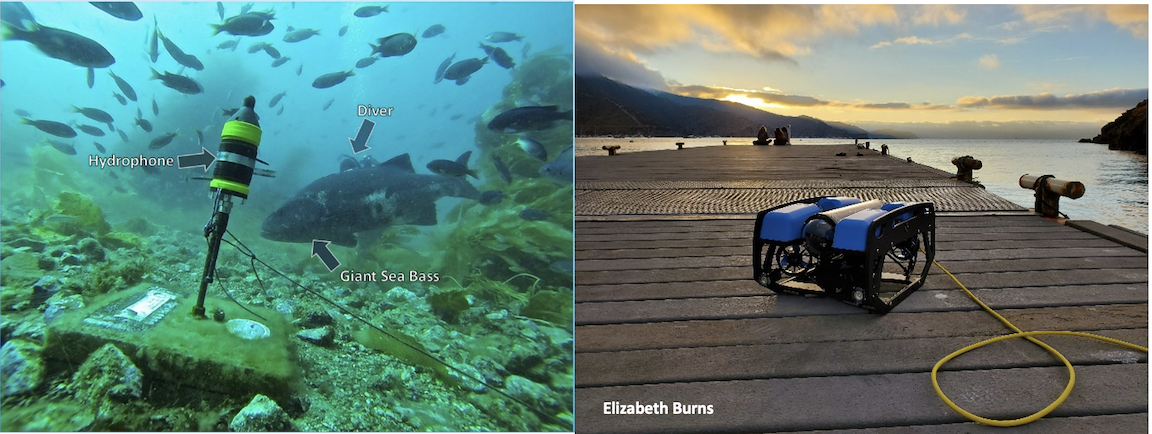

Observing these behaviors requires diving, specialized underwater microphones, and underwater video equipment. This summer, I plan to deploy my equipment and finally find some giants. I have yet to start this year’s field season at Wrigley, but I’m super excited to place my underwater microphones (hydrophones) at spawning aggregations sites. The hydrophones will record sounds in the evening continuously at spawning sites, while my ROV (remote operated vehicle submersible) named Bruce would be used to video record courtship dances with his mounted camera. Unfortunately, due to the pandemic I haven’t been able to really progress with my research until now, since it involves a lot of field work and being away from Catalina has really halted my project.

Left: Hydrophone placed at sample sight in 2014 – 2015. Right: Photo of Bruce on the dock at Wrigley, taken by Elizabeth Burns.

Last summer, I was given the chance to examine Giants’ spawning aggregations sound data gathered by my lab’s alumni and past Wrigley fellows from 2014 – 2015. It is a very difficult task. For one, we don’t know for certain what a boom always sounds like or looks like in the data. Spotting and identifying Giant booms can also be tricky because the hydrophones don’t only pick up Giants sounds, but also other fish, shrimp, divers, boats and various ocean noises.

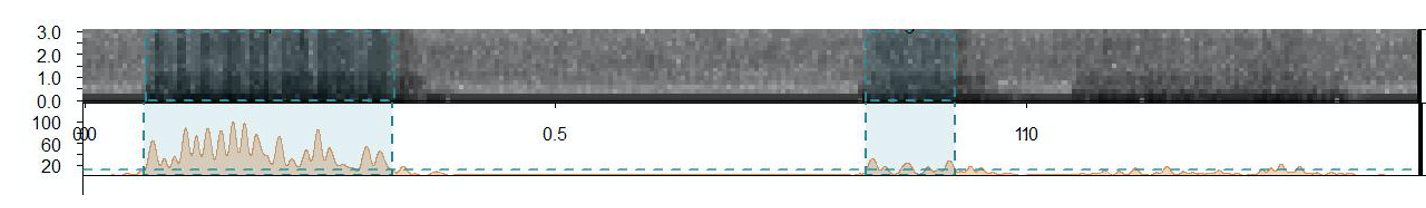

When I examine sound data, I listen to recorded sound clips and I also visually examine them using spectrograms. Spectrograms allow you to visually see signal strength, or “loudness”, of a sound at various frequencies represented as a waveform. These spectrograms allow me to visually quantify the decibels and frequencies of the sounds recorded. Doing this by hand is tricky and time consuming. Luckily, with help, I found a function in the statistical program R (using the package warbleR) that allows me to input parameters that detect booms and it saves me a lot of time.

Shows the waveform and spectrogram of a confirm giant sea bass boom. This spectrogram was made from the program R using the package warbleR.

I am really happy to be back here at Wrigley this year. There is no other place that I could do this fabulous research. This summer I plan to go to Avalon, where I’ll record audio and video of giants at Casino point and Little Farnsworth. So if you see someone with an ROV at Casino Point in Avalon, it is probably me! Feel free to come over and say hi. I’d love to chat with you and show you what I am doing. See you out on the island!