By: Kelley Voss

It’s the last field season of my Ph.D. here at Wrigley. Despite over a year of logistical acrobatics due in large part to a global pandemic, a broken boat propeller, and a dead car, I have finally arrived and, mercifully, I can confidently say I’ve started my best year of field research yet.

This morning started like the rest of my days here this summer: I stumbled out of bed, headed to the kitchen, pouring myself a cup of ambition just like my 6:00 AM alarm instructed me to do (thanks for the wake-up call, Dolly). Every day, my intrepid intern Kristina and I walk down the hill together and get our dive gear set up and loaded onto my dear friend, the trusty, beamy, heavy motorboat known as the Loper.

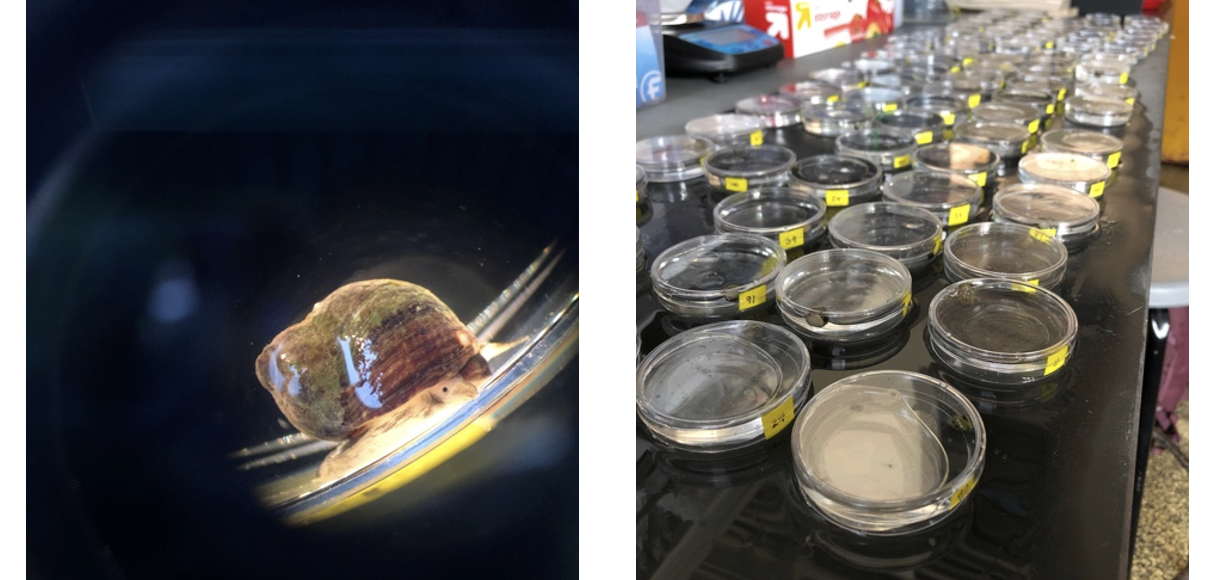

Today was a particularly auspicious day: On our dive, we managed to collect four octopuses in forty minutes, which is far and away my personal best. To catch an octopus, we look through the rocky reefs, using dive lights to peer inside small hidey-holes with freshly cleaned clamshells strewn around them. These octopuses are particularly messy eaters this year! If we find an octopus and it’s not brooding eggs, we squirt a very dilute mix of seawater and white vinegar into the hole and wait for the octopus to come out, gently guiding them into the collecting bag to bring back to Wrigley.

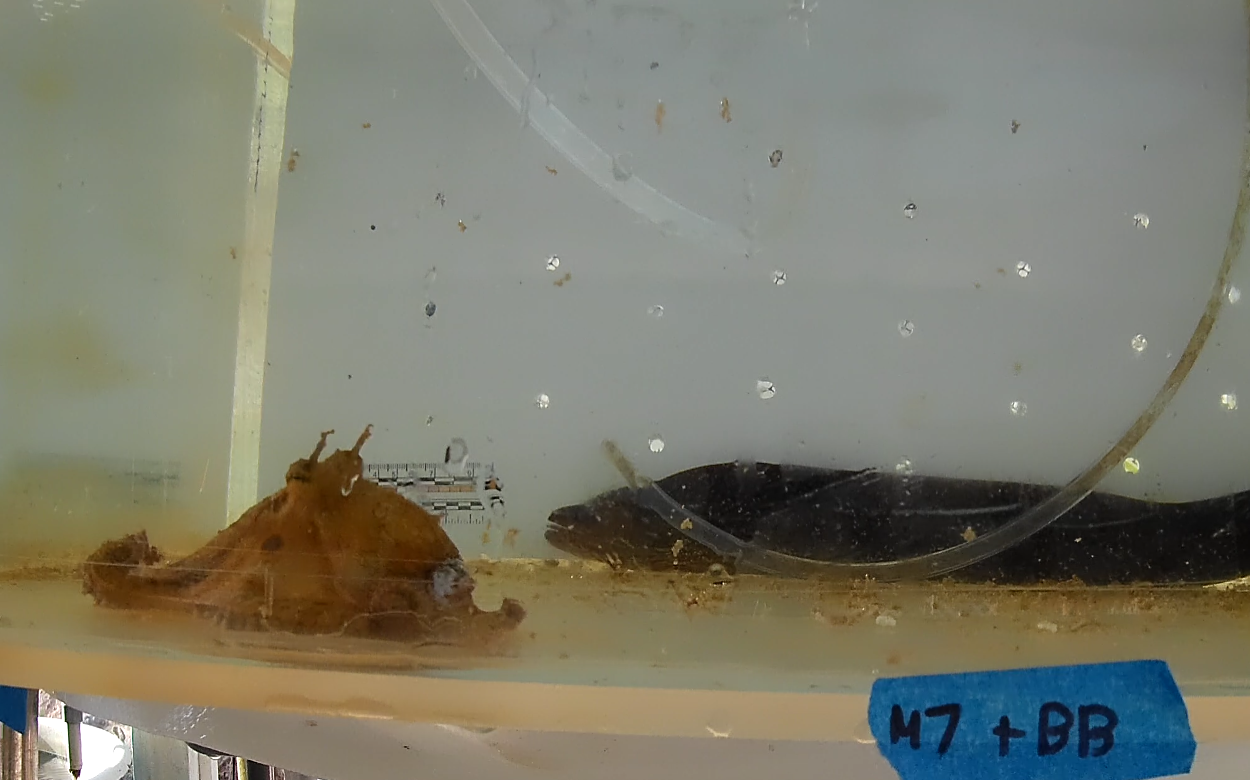

I’ve spent the past two years studying how octopuses (specifically, Octopus bimaculatus) lose their arms when they’re defending themselves against their natural predators, the California moray (Gymnothorax mordax). Not a lot is known about it because it’s a very difficult thing to observe in the wild: it normally happens between dusk and dawn, deep in the crevices of the rocks around the island, between two very cryptic (well-camouflaged) animals.

For my work, we put one of each animal in a tank together about an hour before dusk and record how the octopuses are using their arms to fend off the moray. Kristina reviews the previous night’s videos and collects behavioral data after we get back from diving every morning. While she does that, I’m usually working on some piece of one of my three active doctoral projects until it’s time to set up trials after dinner.

We can film two trials at a time in adjacent tanks. So tonight, Kristina and I will set up interactions between Moray 8 and Octopus GG, and Moray 9 and Octopus HH. There will probably be some moray bites, but don’t worry, we haven’t lost an octopus yet! We expect to see some interesting behaviors, such as males using one arm as kind of a decoy to protect their specialized reproductive arm. We just hope they don’t ink a lot so we can see what they’re doing!

I’ve done a lot of projects at Wrigley over the last decade, and I can’t finish a day in my research life here without expressing my profound thanks for this place. I am so grateful to Wrigley’s staff, some of whom I’ve known for ten years, for all of their support in all my endeavors.

Thank you especially to Trevor for teaching me to drive a boat in 2012, to Lauren O. and Kellie for all the effort they’ve had to put into keeping my various research projects going, and to Juan for always making everything easier and more fun! I also very much appreciate Karen and Lauren G. for helping me with all the logistics of coming and staying here this summer– it was quite a feat! My scientific success and happy memories here are all directly because of all of you.

Before bed, I have to plug four cameras into two computers in order to save all the video footage from that night. Once the videos download onto the hard drive, I’ll take it back to Kristina so she’ll have it in the morning. Walking around the dining hall in the dark, I occasionally get to see a tiny island fox skittering away from the glow of my phone light. If it’s a clear night, I marvel at the starry sky and the gentle sound of water coming in and out of the inky cove. It’s a bit of a grind working from 7:00 AM to 9:00 PM, but what a way to make a living!