By Janet Hu

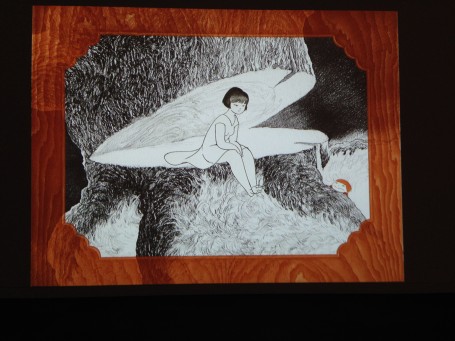

During our stay in Japan, we had many opportunities to try all the great food! In fact, it was always hard to choose what to eat because of all the varieties that are available. Everything always looks special and delicious. Wandering around the streets and food courts, I was particularly intrigued by the “fake” food replicas that can be seen in many shop windows and display cases. Most restaurants display these plastic food replicas in order to attract customers. Moreover, each restaurant has its own custom-made food replicas, which are apparently handmade to look just like the actual dishes offered by the restaurant.

These plastic food replicas have their own interesting history. After World War II, many foreigners came to Japan to participate in the reconstruction process. Due to the language barrier, however, they found it difficult to understand the menus at Japanese restaurants. Therefore, Japanese artisans came up with a way to both display dishes and make them look appealing at the same time: make food sample replicas that won’t spoil and always look appetizing. At first, food sample replicas were made from wax, but because the colors gradually faded when exposed to sunlight, artisans switched to plastic materials instead. Today, food sample replicas are so realistic that I can barely tell they are actually fake!

Here’s a short clip of a food sample artist making some very real-looking lettuce:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tybdEZPZQPk

I was surprised by the sheer variety of plastic food samples available in Japan. There are samples of basically any food you can image, including curry rice, ramen, sushi, fruit, and even beer! We were lucky to visit a street near Asakusa that has become famous for its high concentration of plastic food sample shops. It is called Kappabashi Dougu Street (合羽橋道具街). In addition to the literally hundreds of different kinds of food samples being sold in the many shops along the street, you can also find almost every imaginable kind of tool and equipment used by the restaurant industry on this street. One thing I noticed after handling a few of the plastic food samples was hat food samples tend to be lighter than the weight of the real dishes they represent. This street is definitely an interesting place for those who like Japanese food and are planning to make a souvenir-hunting trip in Tokyo!

In Japan, the craftsmanship of food samples has come to be considered an art form. In fact, some of the best samples are even on display in foreign museums. I find it fascinating how Japan tries to communicate with people in such visual ways. For instance, the warning signs on subways, trains, and buses are usually displayed with accompanying images, which make the signs very easy to understand; the images allow people to receive and understand the information in a very efficient way. Plastic food samples are of course another example. Customers can quickly and clearly understand a restaurant’s menu just by looking at its display of food samples. Moreover, it is also a smart advertising strategy.