By: Lela Ni

The topics of today’s class were the 1954 film Godzilla and the fourth game in the Metal Gear video game franchise, Metal Gear Solid. We examined these two pieces of pop culture through the lens of Japan’s post-nuclear anxieties as a society and nation as well as the parameters of their own art forms. Neva kicked off our discussion with a question about the latter: Why use movies (and other art forms such as literature and video games) to examine historical events? This is a question our class has deliberated on during previous classes, and it was especially topical today because many of the readings related to Godzilla try to move beyond film criticism and examine the movie from a historical perspective. The articles by Igarashi, Anderson, and Noriega offer several different ways we can read Godzilla. Igarashi, for example, introduces the idea that viewers can see Godzilla as a metaphor for the United States and the atomic bomb, and can understand the monster as a projection that helps Japanese society and individuals contend with the events of World War II. Anderson ties this latter interpretation with the concept of the “Other”–people cope with horrific events by casting them into external (and sometimes tangible) things.

Honda Ichiro’s “Godzilla” (1954)

One particularly interesting part of our discussion was Lupe’s insight. Because the movie’s big moral conflict about the A-bomb was distilled into an interpersonal drama between human characters, the movie absolves the larger nation (Japan) from its real-world culpability in World War II. The movie overlooks the fact that such a bomb would realistically require a very expensive and perhaps national effort, and thus Japan as a political entity feels absent from this film even as the film is flooded with images of Japanese people, life, and culture.

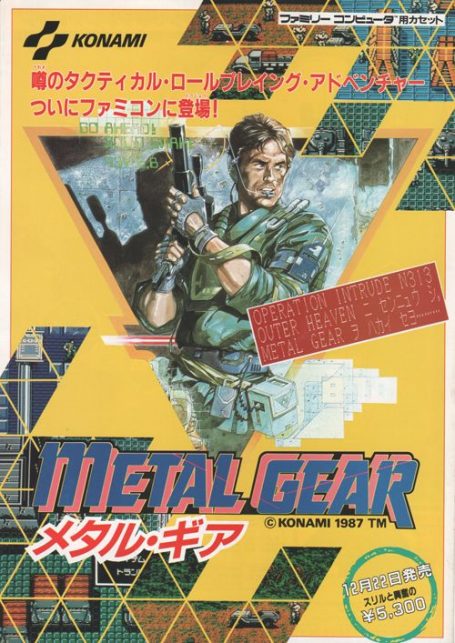

This “erasing” of Japan also occurs in the Metal Gear Solid game, but in this case, it is the ethnic markers of Japan that are removed. Several people brought up good points to explain this: Neva mentioned that video games, unlike films, became prominent during a time of increased globalization. Professor Uchiyama stated that if Metal Gear Solid was too explicitly Japanese, the game’s critiques about American foreign policy would be more difficult/controversial to pull off. There’s also the fact that perhaps the video game creators wanted to make their audience as wide as possible and thought white-washing the Japanese elements would make the game more accessible to non-Japanese players.

Metal Gear Solid – Video Game Franchise

Our class also had a lively discussion about the ontology of video games and how they are so experientially different from films. Whether or not video games (or any other medium or art, for that matter) are an effective means of delivering messages/lessons about the real world is a debate that’s still up in the air, but as Professor Uchiyama stressed in class, it is still important to study the intentions behind these things. Perhaps that is the value of studying fictional historical expressions–the choices involved in the process of creating them can be just as important as the products themselves.

An update on my research project: I’ve decided to go the creative route for my research project. I would like to write a short story in the form of an epistolary, or letters. I’m drawn to this form for this project because letter writing often features the first-person point of view, and this narrative closeness that I will have to develop to the narrator of my story will force me to inhabit her world and circumstances to a degree that a more distant narrator (an omniscient third-person point of view, for example) needs to a lesser extent. I’m not yet sure what the diegesis of these letters is going to be, but I do know that I want to incorporate letters “written” during World War II and letters “written” decades afterward. This is another strength of the epistolary form: you can really compress and expand and leap from time periods, which I want to highlight through my story because this class is, after all, about the memory of war. Aside from these details though, I don’t know what my story is going to look like. My writing process is also a process of discovery, and often I don’t know what I’m really writing about until I begin putting actual words down, so I try to go into a story as blindly and as openly as possible.