The pilgrims wore matching sunshine yellow shirts with the black logo indicating their walk to Fátima. It took them five days from Lisbon; they were blistered and content. It was May 13th, the date of Mary’s first apparition to the three shepherd children in Portugal. I naively asked, “Will you get a certificate?” They smirked and laughed. “No. It is in my heart,” a grizzled pilgrim said, pointing to his heart. I was clearly the crazy American tourist.

Fátima pilgrim on May 13, 2019

In Fátima, the tourist office on the sacred plaza by the Basilicas only offers a Camino stamp. It was my first; it depicted Mary floating on a cloud, three children kneeling at her feet with the scallop shell below and the words Camino de Santiago framing the image. In the days to come I would collect stamps along the Camino. The Catholic Church requires two per day for the last 100 kilometers (for hikers) in order to obtain a certificate of completion in Santiago de Compostela in Spain. This tradition stems from the Middle Ages when pilgrims needed the permission from their pastors, spouses, and employers to set out on the pilgrimage. The pilgrim brought permission letters with them and returned with proof of completion: badges both natural or fabricated – the scallop shell served as proof from Santiago. Since the 1980s the Catholic Church again requires proofs of travel in order to validate the pilgrimage. The stamps serve as that proof.

A pilgrim passport with stamps from along the Way

Some pilgrims take the stamps seriously. A German-Vietnamese pilgrim went from hostels to cafés, post offices, police stations and churches gathering many per town. Pilgrims collect stamps like a birder has a life list or climbers are referred to as “peak baggers.” I met a pilgrim walking back from the Herbón monastery and her only comment was, “I got the stamp.” In the monastery at Armenteira one nun carefully explained their stamp to me with pride. “A monk – there used to be monks living here- went to the garden to pray to God. See here is a little bird in the tree (she points to the elaborate stamp). He stayed 300 years and when he returned to the monastery none of the monks knew him.” She concluded with an explanation, “When you are in communion with God … (there is no sense of time).” The stamp grew in meaning for me. One morning at the Evangelical homestay, Debbie explained that the previous year she did not have a stamp. She would draw in the pilgrim’s Camino passport. Then as a surprise one pilgrim got her drawing made into a stamp back home for her. She used this now.

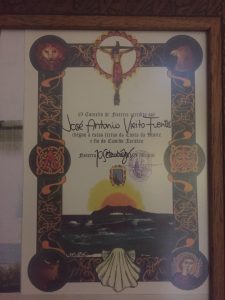

When the pilgrim passport is filled with colorful shapes – sometimes sideways, smeared, overlapping or sweat soaked, it is presented for inspection to the Roman Catholic Church office in Santiago. The Church will only issue the Compostela to those who have the requisite number of stamps and who did their pilgrimage on foot, horseback or on bicycle. This certificate is a printed, decorative “medieval” manuscript in Latin with your name, translated into Latin, written with a calligrapher’s flourish in the center. Once again the Church has taken over the authority to confirm who is a “real” pilgrim.

The author with her daughter Marika showing off the Compostelas in 2015.

The lure of formal documents rewarding the pilgrim has begun to infect the Camino de Santiago with a consumerist air. Galician certificates multiply. The Spanish offer certificates for completing half of the French route (San Jean to Burgos?), for walking into Padrón and another for going to the Herbón monastery nearby,

Herbón monastery certificate. They leave it to the pilgrims to fill in their own names.for walking from Santiago to Finesterre/Fisterra on the coast, another for walking into Muxia. The more certificates that are issued the less they seem to have value. Maybe the Fátima pilgrims were right. We should confirm the pilgrimage in our hearts rather than on paper.

for walking from Santiago to Finesterre/Fisterra

Fisterra certificate

on the coast, another for walking into Muxia. The more certificates that are issued the less they seem to have value. Maybe the Fátima pilgrims were right. We should confirm the pilgrimage in our hearts rather than on paper.

The silky shimmer of sea as it calls along the shore

The silky shimmer of sea as it calls along the shore With the Camino de Santiago being rooted in Catholicism, one would most likely assume that the main reason for walking is religious or spiritual. After all, pilgrims walk hundreds of miles to arrive at the place where Saint James’ bones are supposedly residing in a silver coffin. When walking a pilgrimage in medieval times, you may have found many pilgrims walking to repent for their sins. But, also in medieval times displayed a large flux of reasons people would walk. Sometimes, those had no option. If a crime was committed, a viable sentence would be to send the guilty on a trek. This could be seen as a form of punishment, or a second chance to connect with God and right your wrongs. In contrast, one may have walked a Pilgrimage to escape from the plague, or conquer famine. A quote from Pilgrimage in Medieval Culture recites “Santiago de Compostela became above all a goal of the devout and the voluntarily and involuntarily penitent rather than a healing shrine.”

With the Camino de Santiago being rooted in Catholicism, one would most likely assume that the main reason for walking is religious or spiritual. After all, pilgrims walk hundreds of miles to arrive at the place where Saint James’ bones are supposedly residing in a silver coffin. When walking a pilgrimage in medieval times, you may have found many pilgrims walking to repent for their sins. But, also in medieval times displayed a large flux of reasons people would walk. Sometimes, those had no option. If a crime was committed, a viable sentence would be to send the guilty on a trek. This could be seen as a form of punishment, or a second chance to connect with God and right your wrongs. In contrast, one may have walked a Pilgrimage to escape from the plague, or conquer famine. A quote from Pilgrimage in Medieval Culture recites “Santiago de Compostela became above all a goal of the devout and the voluntarily and involuntarily penitent rather than a healing shrine.”

Liminality, as first defined by anthropologist Victor Turner, is a process of being in-between. Having left a previously held structure, the person then exists in an area of ambiguity until their rite of passage, journey, or pilgrimage is complete. Turner would argue that most pilgrims exist in that liminal space. It is how we as a class have existed for the length of our journey – walking for two weeks from place to place, never quite finding structure or finality. However, contrary to Turner’s definition, many pilgrims do not always find themselves in this liminal space for the extent of their pilgrimage. Many have walked the Camino multiple times, incorporating it repeatedly into their lives. I met a man from Colorado who was on his fifth Camino – since he’s retired this has become his yearly routine. Even more extreme is the case of a Dominican monk from Poland, who claims to have gone on the Camino six different times with different groups of students. While on the pilgrimage he provides them with a daily mass, leadership, and guidance. For these people, the pilgrimage has become a routine, something they do time and time again, year after year. I would argue that these people still exist in liminality – after all, they are on the move without a structured sense of here or there. But the Camino has also become a type of structure for them, putting them at an interesting in-between. From these pilgrims, it would be simple to assume that pilgrimage necessitates some degree of liminality; however, in certain cases it can provide a deep and permanent structure. Such is the case with Rita, an Irishwoman who runs a pilgrimage house with her husband Matthew. For Rita, her pilgrimage started much earlier than the Camino – leaving her job and life behind at twenty-one to travel to Amsterdam and escape her current structure. In Amsterdam, she met a man who invited her into the church community located there, where she eventually found structure and a return to her faith in God. Now, she runs a pilgrim hostel in which she gifts a part of her experience unto others, making a safe, clean place for many pilgrims to relax, rest their aching feet, and spend the night. Pilgrimage for her is no longer a liminal space per Turner’s definition – there is no real in-between and she has long since completed any specific rite of passage. The Camino has instead become a structure on which she has built the foundation of her life. Thus, as the pilgrim saying goes, “The Camino provides”. A freedom and ambiguity for first time walkers, a consistent adventure for returning pilgrims, and even a sense of permanent community.

Liminality, as first defined by anthropologist Victor Turner, is a process of being in-between. Having left a previously held structure, the person then exists in an area of ambiguity until their rite of passage, journey, or pilgrimage is complete. Turner would argue that most pilgrims exist in that liminal space. It is how we as a class have existed for the length of our journey – walking for two weeks from place to place, never quite finding structure or finality. However, contrary to Turner’s definition, many pilgrims do not always find themselves in this liminal space for the extent of their pilgrimage. Many have walked the Camino multiple times, incorporating it repeatedly into their lives. I met a man from Colorado who was on his fifth Camino – since he’s retired this has become his yearly routine. Even more extreme is the case of a Dominican monk from Poland, who claims to have gone on the Camino six different times with different groups of students. While on the pilgrimage he provides them with a daily mass, leadership, and guidance. For these people, the pilgrimage has become a routine, something they do time and time again, year after year. I would argue that these people still exist in liminality – after all, they are on the move without a structured sense of here or there. But the Camino has also become a type of structure for them, putting them at an interesting in-between. From these pilgrims, it would be simple to assume that pilgrimage necessitates some degree of liminality; however, in certain cases it can provide a deep and permanent structure. Such is the case with Rita, an Irishwoman who runs a pilgrimage house with her husband Matthew. For Rita, her pilgrimage started much earlier than the Camino – leaving her job and life behind at twenty-one to travel to Amsterdam and escape her current structure. In Amsterdam, she met a man who invited her into the church community located there, where she eventually found structure and a return to her faith in God. Now, she runs a pilgrim hostel in which she gifts a part of her experience unto others, making a safe, clean place for many pilgrims to relax, rest their aching feet, and spend the night. Pilgrimage for her is no longer a liminal space per Turner’s definition – there is no real in-between and she has long since completed any specific rite of passage. The Camino has instead become a structure on which she has built the foundation of her life. Thus, as the pilgrim saying goes, “The Camino provides”. A freedom and ambiguity for first time walkers, a consistent adventure for returning pilgrims, and even a sense of permanent community.