As far as introductions go, those along the Camino de Santiago are simple, consisting of each person’s name and country of origin. Along The Way, I was “Reem from the United States.” With this I was surprised to learn that as an American, most pilgrims were fascinated to learn about my thoughts on Donald Trump and the entire Trump administration. This interest may stem from the disastrous nature of the current administration, or simply from other nation’s engrossment with American pop culture and politics. Regardless, the Trump inquiries followed me along the Camino. So, in an attempt to turn the tables, I decided to ask pilgrims along the Camino about their thoughts on President Trump and the United States, in general.

Der, from Ireland, has lunch with us our first day on the Camino

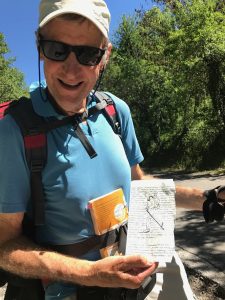

One of my first Camino friends,“Der from Ireland,” an engineer for an American pharmaceutical company and an American history buff, walked along the Way with me and discussed American politics. I brought up the Trump administration and Ireland’s view of the president and he simply laughed. According to Der, the majority of people see the president in a negative light. He explained to me that various American corporations, including the pharmaceutical company he works for, receive tax benefits by occupying headquarters in Ireland. These companies also simultaneously boost the Irish economy and employ many Irish citizens. Trump’s campaign promises to lower taxes in the U.S. will greatly affect the Irish economy when American companies relocate back to the U.S., leading Ireland to lose foreign investment. Thus, the Irish are not big fans of the Trump administration and its future plans. Der added, “Americans are smart. They sent people to the moon, for heaven’s sake.” But, he slyly implied that Trump’s election was a poor choice made by the “smart” Americans.

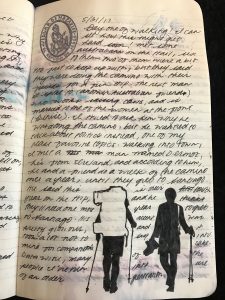

A Spanish man in his 40s called Trump an “economic dictator” focused only on elevating America’s world status, rather than the wellbeing of the nation. He emphasized that it was quite a shock to the Spanish population when such a man was elected. After voicing his disapproval of Trump, he said, “I miss Obama and wish he ran for another term” and “I hope Michelle runs in 2020,” which both came as a surprise to me. I did not expect him to be so up to date with American politics and to support the former president so freely. Ironically, we had this discussion the day the Spanish President was ousted from office.

While discussing the newly impeached Spanish President and inauguration of the leader of the Spanish socialist party as the new Prime Minister of Spain, a 25 year old British woman asked me when I thought Trump would be impeached. She even went on to ask if I thought he would be assassinated. I did not know how to answer these questions other than to say, “With Trump gone, we get Pence, and we don’t want that.” She told me she believes that Spain’s government issues are a foreshadowing of problems brewing in the U.S. Regardless, I was genuinely intrigued by all the parallels pilgrims were drawing between the failing Spanish government and America’s government.

A German woman in her 60s shared with me that “Germans do not like Trump because Merkle does not like him.” She elaborated that when Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor, went to the White House to meet President Trump, he refused to shake her hand. Following, the entire German nation went “crazy” and since then has greatly disliked the U.S. President. They feel Trump’s insecurity and need to appear powerful are what kept him from shaking Merkel’s hand, and this mentality makes him a poor leader.

Author with her German pilgrim friend

Along the Way, I found it very interesting that so many international people were concerned with American politics, gossip, and the Presidential Administration. I learned that it can be a little uncomfortable to ask about Trump and American politics, especially as someone who is not particularly fond of him or his work. But, ultimately, discussing politics was a nice way to connect with pilgrims on the Camino and learn how our government affects their country. I was asked a few times whether or not Trump might be elected for a second term. I imagine it will be interesting to discuss the upcoming U.S. election/re-election in 2020 on the Camino.

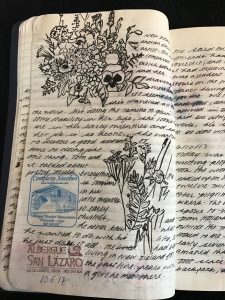

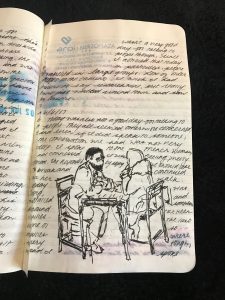

Arturo, the owner of the quaint and colorful albergue, offered us a tour, gave us canvases to paint on, and even greeted me in Korean. He epitomizes the community spirit of the Camino and his remarkable story is an example of why I wanted to participate in this trip.

Arturo, the owner of the quaint and colorful albergue, offered us a tour, gave us canvases to paint on, and even greeted me in Korean. He epitomizes the community spirit of the Camino and his remarkable story is an example of why I wanted to participate in this trip.

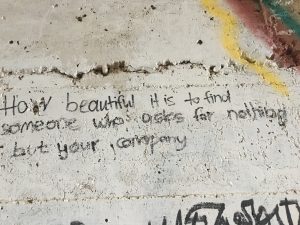

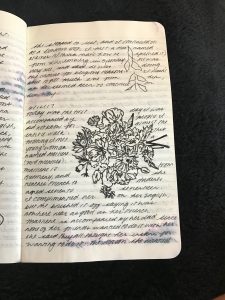

I have always been amazed by the beauty of the natural world. To me, there are different kinds of nature: plants free to grow, animals free to roam, even people with a cup of coffee in a cafe.

I have always been amazed by the beauty of the natural world. To me, there are different kinds of nature: plants free to grow, animals free to roam, even people with a cup of coffee in a cafe.

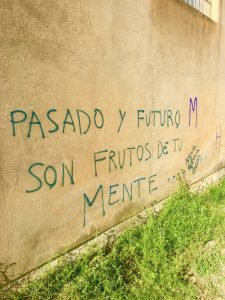

About five minutes after leaving Leon on my first day of pilgrimage, I can across a

About five minutes after leaving Leon on my first day of pilgrimage, I can across a