By: Alexandra Stella

Hello! My name is Alexandra Stella and I am currently a Senior at the University of Southern California! I am majoring in Environmental Studies and minoring in Political Science and Marine Biology.

My summer as a Zinsmeyer Intern at the USC Wrigley Marine Institute was filled with new experiences and unforgettable memories. I had the opportunity to work on two projects- researching sex change in blue banded gobies with Dr. Devaleena Pradhan and analyzing the health of eelgrass beds off the coast of Catalina Island with Dr. Dave Ginsburg. Most of my days started off early in the morning scuba diving to collect samples or data. After that, I’d move into the lab for fish processing or eelgrass data analysis!

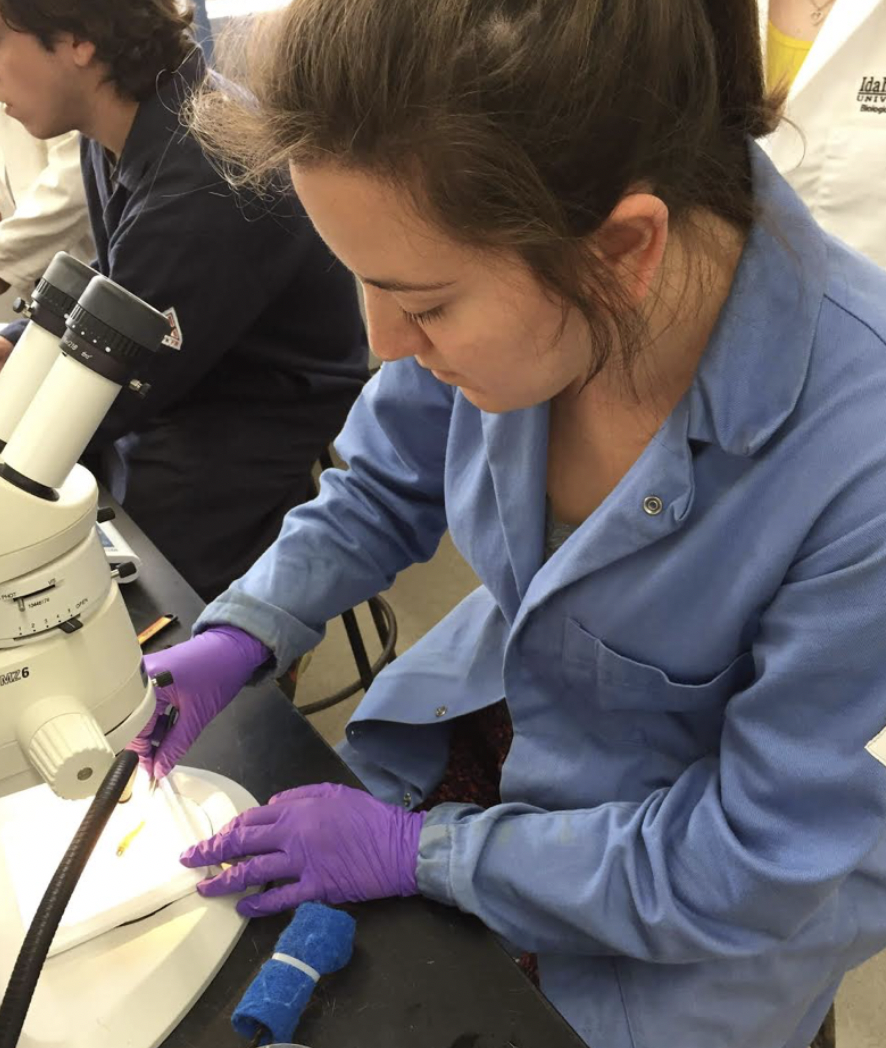

My work with Dr. Pradhan required me to obtain a variety of new skills – from our special in-field fish capturing technique, to taking correct fish measurements for processing, to learning how to dissect the fish, to watching fish behavior, to even small tasks like labelling a centrifuge tube correctly (a very important step, I might add!). Overall, our goal with this summer research was to identify stressors that cause significant morphological and/ or behavioral changes in the gobies. We focused a lot of our time recording fish behavior in response to our test conditions to learn more about the gobies’ individual and group responses to change in the hierarchical make-up of their social groups. Understanding the effects of certain environmental conditions can lead us to a greater understanding of the survival and fecundity of this species which in turn has an impact on its surrounding ecosystem as these fish serve as an important prey source.

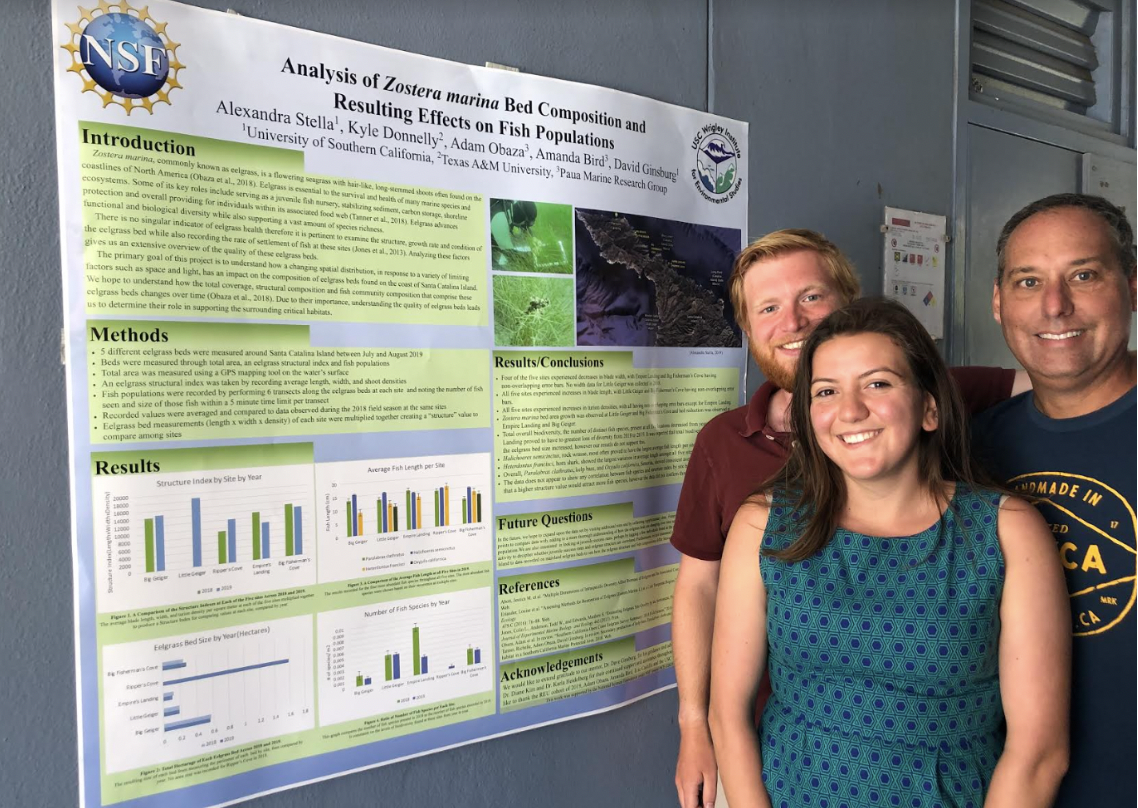

My second eelgrass project dealt with more management/ conservation issues. Eelgrass is often overlooked as insignificant in terms of the health of the entire ocean. But Dr. Ginsburg’s team recognizes how critical it is to the success of nearby habitats, and so dedicate themselves to study the health of the beds off Catalina Island. We performed various tasks underwater at multiple sites such as bed mapping and density data collection which involved recording the eelgrass length, width and height. Once we documented this information and compiled the data, we were able to compare it to last year’s data (the first year of this project) to understand how the health of the beds has adjusted over time. My work on this project is only one data point on what will hopefully be a large, comprehensive dataset as we continue to collect data year to year. Dr. Ginsburg’s project provides baseline data for eelgrass beds off the coast of Catalina – once completed, it will hopefully bring to light the significance of eelgrass for the health of other habitats in the ocean!

I learned so much this summer and am very grateful for these hands-on experiences! It feels so rewarding to walk away with a multitude of new skills and knowing you have added a point of discussion to some critical environmental research!