By: Erin McParland

Hello! My name is Erin and I am a PhD candidate in the Marine and Environmental Biology Department at USC. I am currently finishing my final thesis experiments at the Wrigley Marine Science Center (WMSC), thanks to the Wrigley Institute’s Bakus Graduate Research Fellowship!

The last chapter of my thesis aims to understand how interactions between microscopic organisms in the surface ocean may influence organic carbon cycling. Even though we can’t see it happening, phytoplankton (microscopic plants) and bacteria are constantly ‘talking’ to each other in the ocean. Sometimes this involves sharing nutrients, and other times competing for nutrients. These nutrients are part of the organic carbon pool, which stores the same amount of carbon as atmospheric carbon dioxide, and therefore plays a very important role in controlling Earth’s climate!

What controls the production and consumption of the organic carbon pool in the surface ocean is still not fully understood, and is an active area of research in oceanography. My research combines lab and field experiments to ask if these microbes are trading a particular carbon compound: DMSP (dimethylsulfoniopropionate). DMSP is produced by phytoplankton, and quickly assimilated by microbes because it is both a carbon and sulfur compound, making it a particularly yummy component of the organic carbon pool.

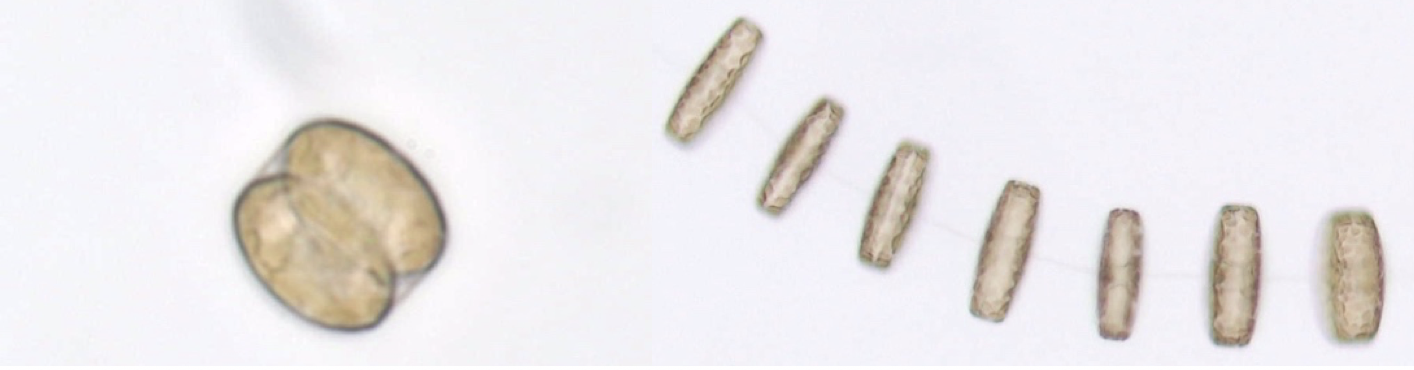

Microscope pictures of diatoms that make DMSP. On the left is a single cell, on the right are multiple cells connected in a chain.

To answer my research question, I have spent a lot of time in the lab trying to grow phytoplankton cultures without bacteria. To accomplish this I add antibiotics to seawater, just as humans take antibiotics when we have a bacterial infection. This might seem like an easy task, but for the phytoplankton these bacteria are not infectious, but rather symbiotic. Some of the phytoplankton just can’t grow without their bacterial partners. Now that I have finally successfully grown phytoplankton bacteria-free, I can conduct my experiments.

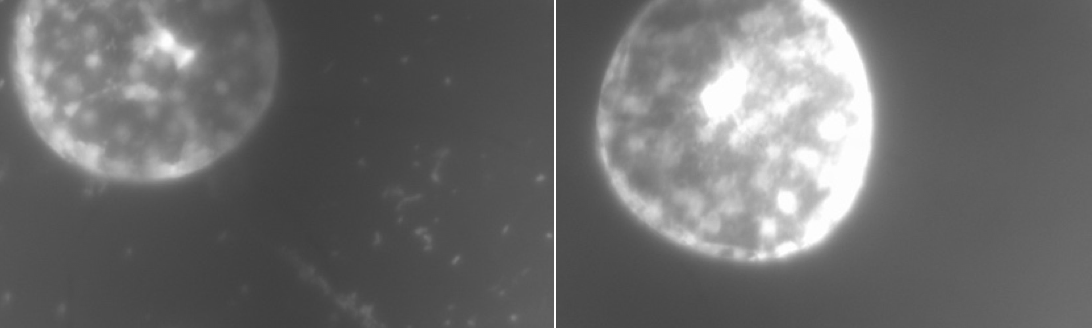

Diatoms (big circles) growing with bacterial partners in the surrounding water (small white dots in the black background) (left) and without bacteria (right).

I’m going to WMSC to collect natural seawater at Catalina, which has roughly 1 million bacteria cells per milliliter of seawater! I will filter the water either to be clean seawater (with no bacteria) or bacteria-filled seawater, and will measure the production of DMSP as I add the two types of seawater to my phytoplankton. I hypothesize that the phytoplankton will make more DMSP in the bacteria-filled seawater to trade this yummy compound for other nutrients that only bacteria can make, such as vitamin B12.

These experiments will be the first evidence for differences in phytoplankton DMSP production, based on the presence or absence of bacterial partners. The results will improve our understanding of the role of microscopic interactions in organic carbon cycling in the ocean.