By: Maria Ruggeri

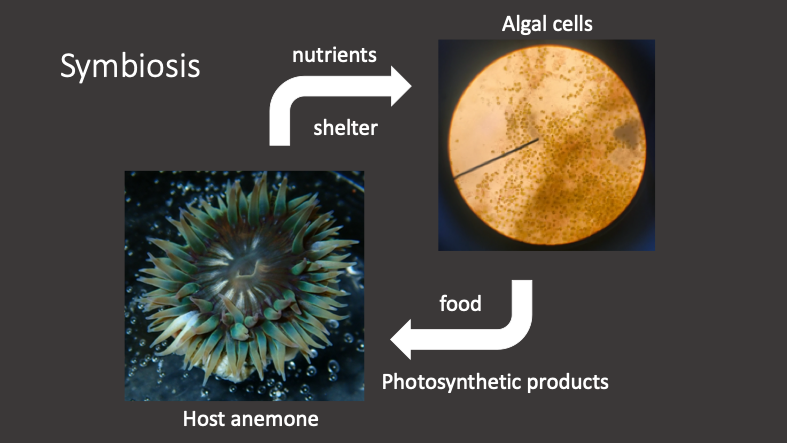

Hello everyone! My name is Maria Ruggeri and I am a 4th year PhD student at the University of Southern California. This year I received the Victoria J. Bertics Summer Fellowship to study how sea anemones and their algal partners survive in extreme environmental conditions. The sea anemone, Anthopleura elegantissima, is very common along the coast of California. These anemones may look like underwater flowers, but they are actually animals! However, they do get their energy from photosynthesis… How you may ask? They have microscopic algae that lives within their tentacles! The host anemone provides nutrients and shelter to the algae in return for photosynthetic products that it can use as food (Fig 1). Therefore, this relationship is mutually beneficial to both partners.

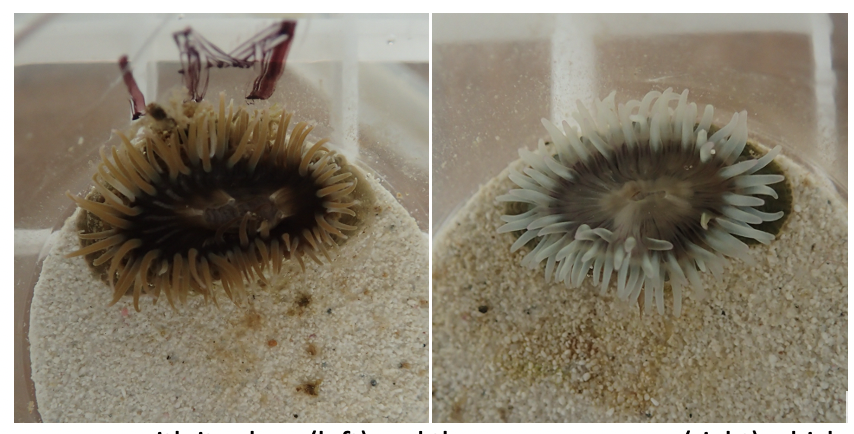

Unfortunately, in stressful conditions, this partnership breaks down and algae is expelled from the host in a process known as bleaching. The absence of algae causes the anemone to appear white, which gives this response its name (Fig 2). Bleaching can occur due to a variety of environmental stressors, but I am particularly interested in temperature. In tropical corals, which are closely related to sea anemones, bleaching can ultimately lead to death and occurs only 1-2°C above average summer temperatures. Increasing temperatures due to climate change have already cause worldwide declines in coral cover. However, the anemone I am studying can survive temperature increases of up to 20°C!! I am interested in studying the mechanisms sea anemones and their algal partners use to cope with these extreme temperatures to help predict how corals may adapt to future ocean conditions.

Figure 2: Healthy anemone with its algae (left) and the same anemone (right) which was bleached due to high temperature stress.

These sea anemones are also really interesting because they can reproduce asexually to make multiple clones of themselves, which stay together to form large anemone aggregations (Fig 3). Previous research found that anemones on the inside of these aggregations are buffered from high temperature stress by their clonemates on the outside. This allows us to study whether preconditioning to higher temperatures makes individuals more resistant to bleaching, without

any genetic changes. Alternatively, we can also study whether non-clonal anemones respond differently to temperature based on their genetic differences.

Although I was unable to get out to the island this summer to run bleaching experiments, I kept busy by analyzing another dataset on bleaching in tropical corals. Now that the Wrigley Institute is opening back up its doors to researchers, I will be going out in November to run an experiment to study bleaching within clonal groups and across genetically different aggregations to tease apart the contribution of ‘nature’ versus ‘nurture’ in increasing thermal tolerance.