By: Emily Ryznar

Hello! My name is Emily Ryznar. I am a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at UC Los Angeles and currently a Graduate Summer Fellow with the Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies.

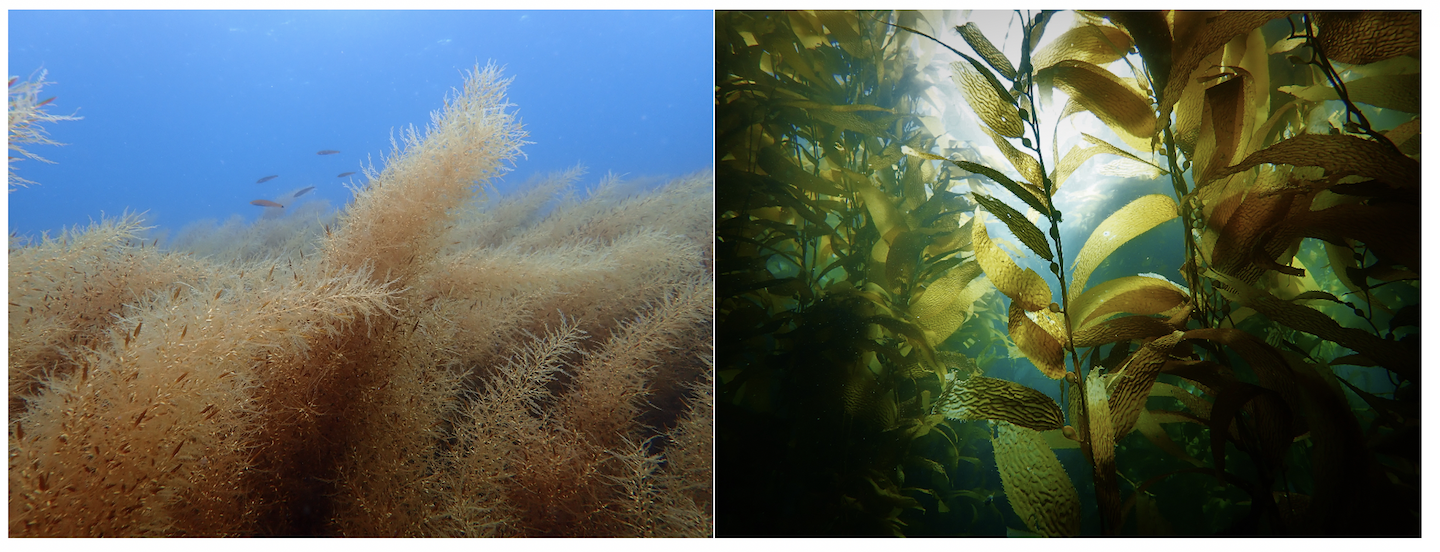

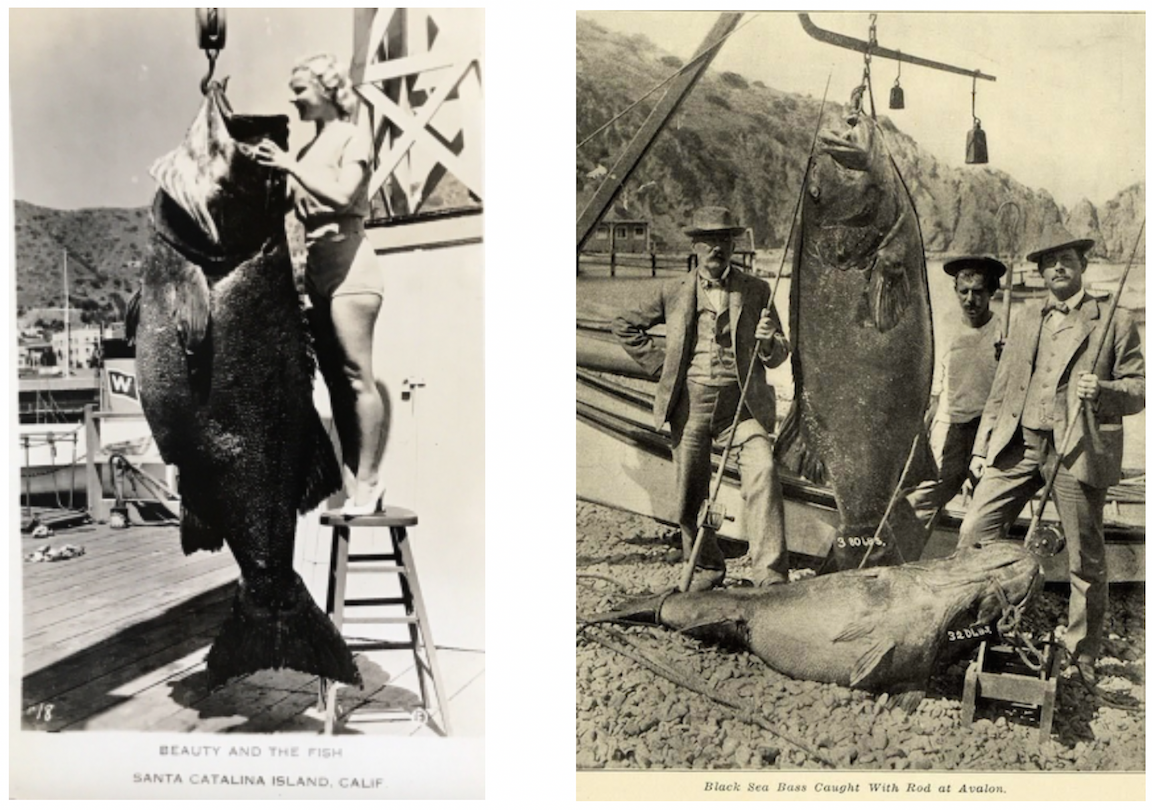

For my dissertation, I am researching mechanisms that may enhance community susceptibility to invasion and facilitate the success of the invasive brown alga, Sargassum horneri. S. horneri is native to South Korea and Japan and arrived in Long Beach Harbor in 2003. Since it’s arrival, it has since spread throughout the Channel Islands, north towards Point Conception, and south into Baja California. Despite its seemingly rapid proliferation and current widespread range, little is known about how S. horneri is impacting native species, why S. horneri is so successful in Southern California when compared to other non-native species, and whether certain communities are more or less susceptible to invasion. Knowing this is particularly critical as widespread eradication of S. horneri is likely unfeasible. Thus, understanding S. horneri’s impacts and identifying vulnerable communities may facilitate more rapid and effective management of S. horneri’sspread before it becomes established in new areas.

That’s where my research comes in! I am currently investigating two main questions: 1) What factors enhance community susceptibility/resistance to invasion by S. horneri? and 2) How is S. horneri interacting with native giant kelp, or Macrocystis pyrifera?

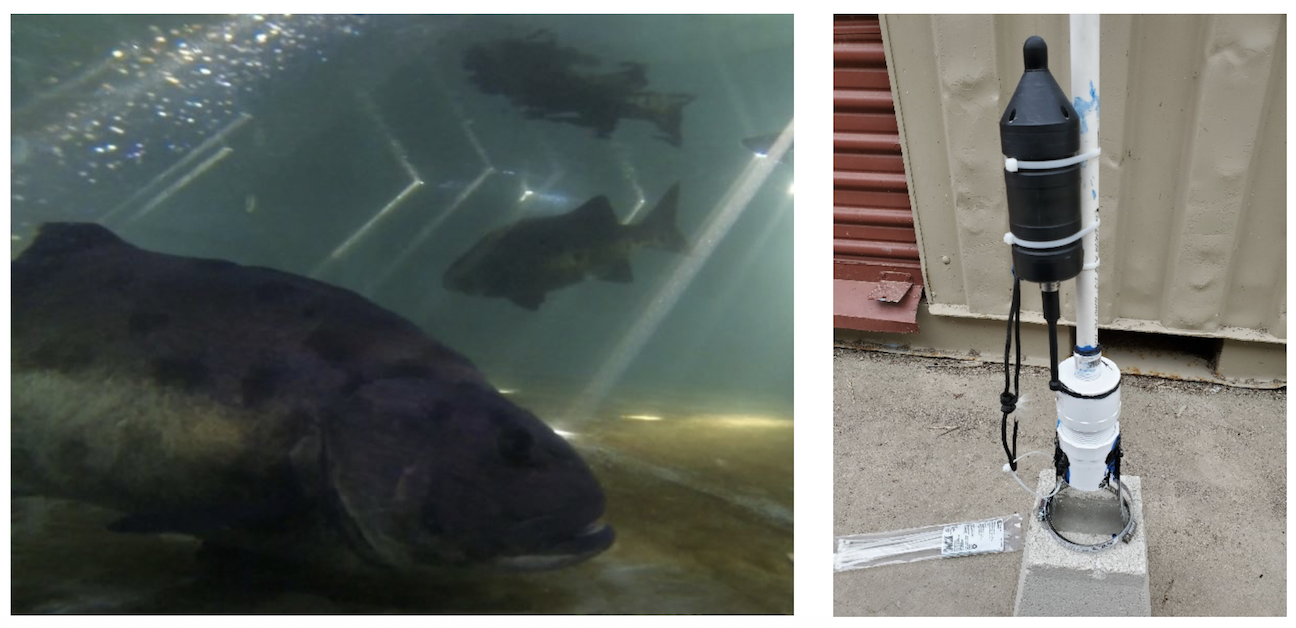

For my first question, recent research has concluded from long-term data that herbivory and competition with native algae can enhance community resistance to S. horneri invasion on Anacapa Island in the Northern Channel Islands. To ground-truth these conclusions in the field and in the Southern Channel Islands, I have been running a series of field experiments comparing S. horneri growth in areas with high levels of herbivory and areas with strong competition from native algae on Catalina to evaluate whether herbivory or competition can determine S. horneri success and community susceptibility. Therefore, areas where S. horneri exhibits the greatest growth are likely the most vulnerable to invasion while the opposite is true for resistant communities. Excited to see what the data shows!

For my second question, I conducted several field experiments over the winter where I transplanted different life-history stages of S. horneri and giant kelp into 3 different, adjacent site types: 1 site dominated by S. horneri, 1 site dominated by giant kelp, and 1 site devoid of algae. I also monitored light and temperature at each of these sites. These experiments allowed me to evaluate how competition for light/space can influence the survival and success of giant kelp and S. horneri. I was also able to draw conclusions as to how dense S. horneri beds can inhibit giant kelp survival, how healthy giant kelp forests may be able to prevent S. horneri spread, and if open space becomes available, how the growth of S. horneri and giant kelp compare if they trying to colonize that space. Basically, it is an arms race that S. horneri is seemingly winning.

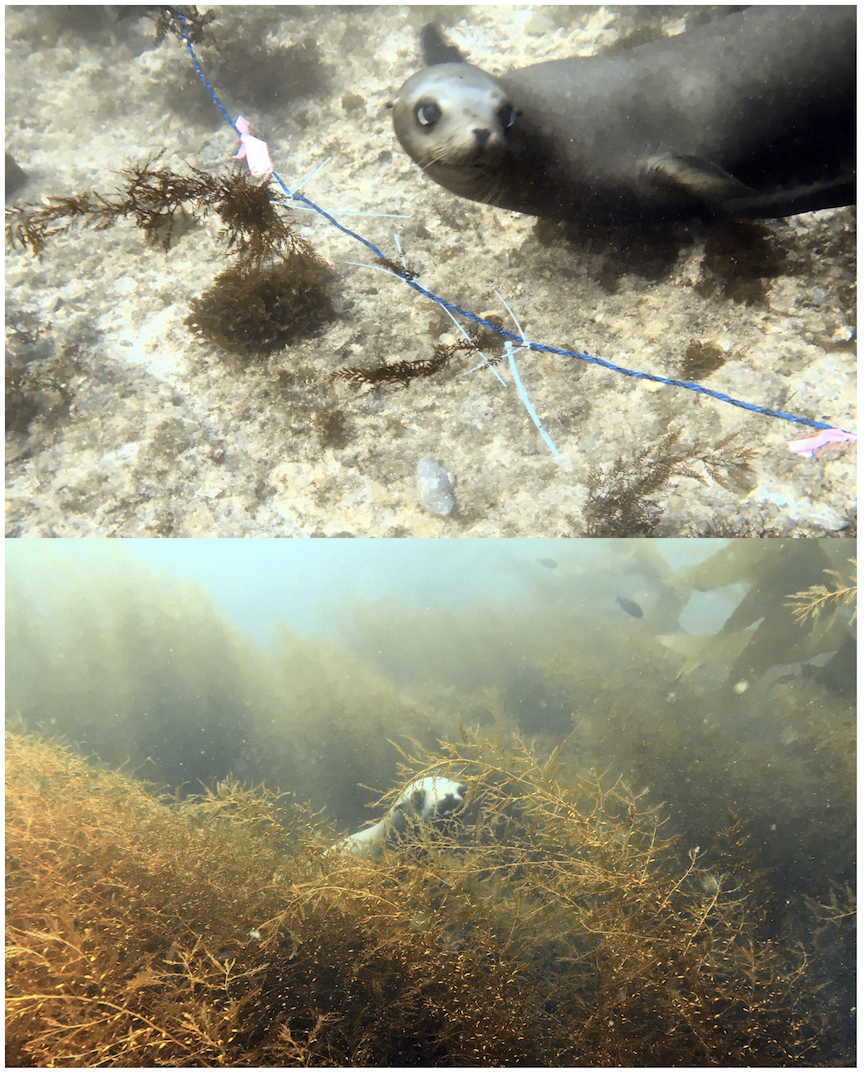

Almost all my research is conducted via SCUBA, so I get to spend a lot of time underwater! Surprisingly, I’ve made many sea-dwelling friends like the sea lion pictured below. He provides quality control for my field experiments and even plays hide-and-seek when we have some down time. I’m forever thankful that my research allows me to experience moments like these!

A sea lion providing quality control for one of my experiments (top) and playing hide-and-seek in a Sargassum horneri bed (below). Photo credit: Kelcie Chiquillo.

If you have any questions or want to learn more, feel free to email at emilyryznar@gmail.com. Thanks for reading!