By: Charnelle Wickliff

Hello everyone! My name is Charnelle and I am entering my 3rd year of my master’s program at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories. I am co-advised through CSUMB by Dr. Corey Garza and Dr. Alison Haupt. It is unfortunate that I am not able to come out this summer to hike, snorkel, enjoy the island life, and fly a drone from the beach. I have been keeping myself busy by working on refining my thesis proposal, reading research papers, and analyzing data.

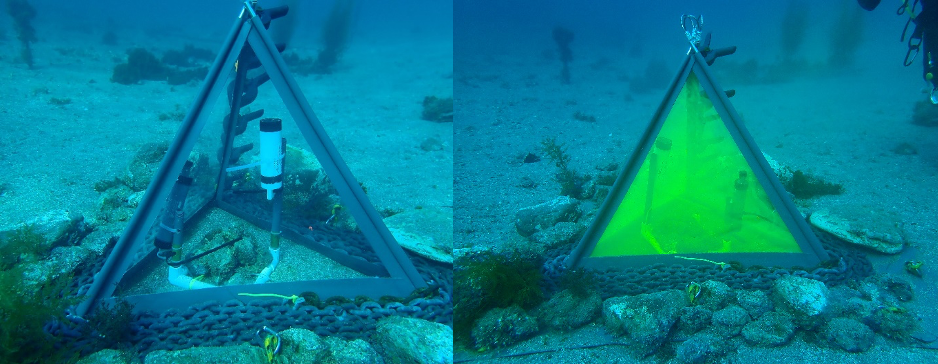

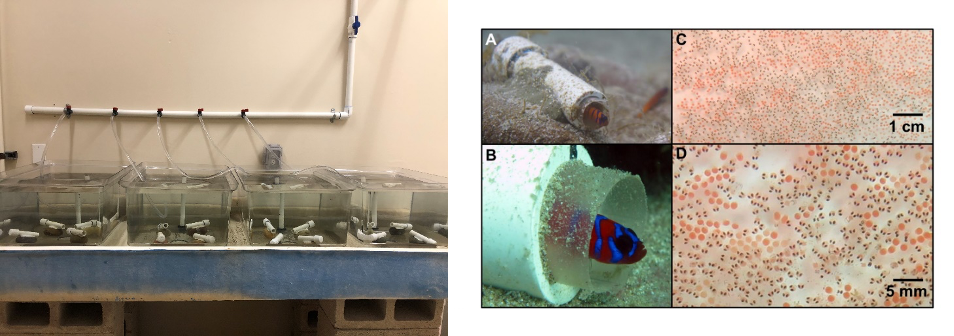

My research focuses on drones, and how they can be a great tool in monitoring subtidal habitats, like rhodolith beds (a free-forming benthic calcifying red coralline algae) on Catalina. My interest in drones – other than their cool factor – stems from my undergraduate experience at CSUMB building and operating remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and a capstone project building an autonomous buoy that can station-keep for small boat deeper waters. I became interested in rhodoliths after being introduced to Dr. Diana Steller at MLML and her colleague Dr. Matt Edward at SDSU. I learned from them and literature that rhodolith beds are beaming with life from worms, juvenile urchins and snails, and so much more.

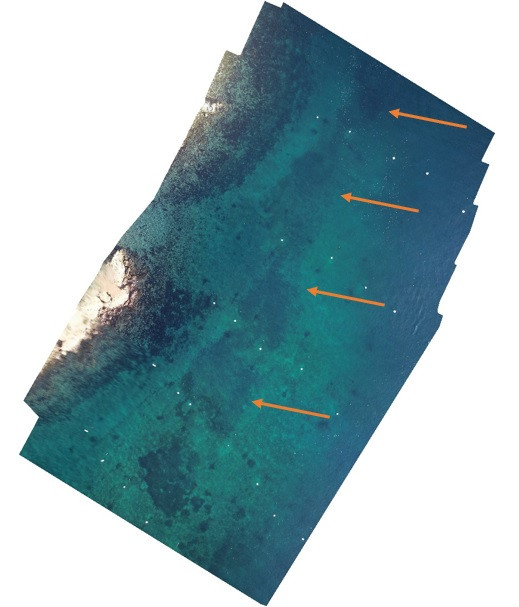

Image of Isthmus rhodolith bed January 2020. Taken from 70m high. Orange arrows point to the Isthmus bed.

Rhodolith beds maybe important nursery ground to the local rocky intertidal community, I want to know if these beds are subjected to seasonal changes and if they are heavily affected by mooring chains. I want to know if it is possible for a drone to capture the rhodolith beds and detect spatial and temporal changes.

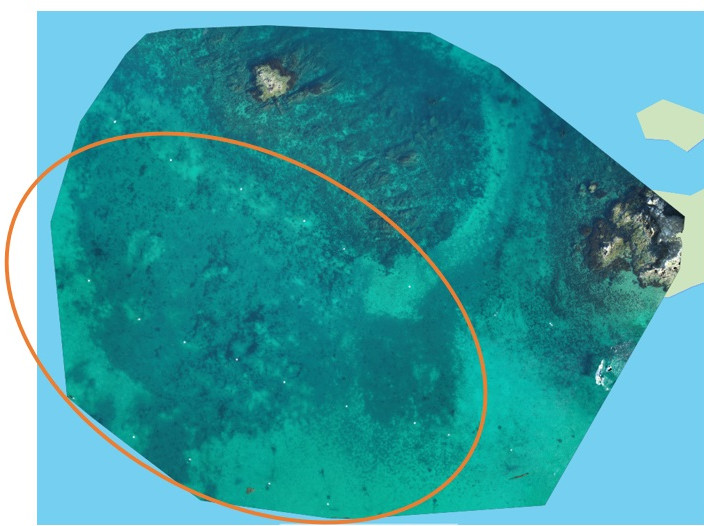

Catalina Island has 7 beds within 6 different coves. I will be comparing dive surveys and drone imagery in their ability to detect and measure changes of Emerald Bay and Isthmus beds. I am looking for changes in the perimeter (edge) and cover (total area and live rhodolith percent cover).

Image of the rhodolith bed at Emerald Bay January 2020. Taken at 70m high. Orange circle is around the bed at Emerald Bay.

I was able to collect my first set of photos in January 2020 by flying a Phantom 4 drone using Pix4d software. The plan was to collect aerial photos every season for 1 year of Emerald Bay and Isthmus rhodolith beds. With COVID-19, I am pushing back my data collection and hoping to return as early as this fall or January 2021. I am using ArcGIS to process my images by measuring area and detecting perimeter and area changes once more data is collected.