By: Elise Steinberger

A clever biochemistry professor once asked myself and other students, with a clever smirk, where the cure to cancer was. Baffled, most people assumed they misheard the question – as it implies there exists a location where the cure to cancer lies hidden and, if only we could pinpoint it we would be set. After watching the students squirm for a few seconds, the professor said ‘coral reefs.’ Some of the students whispered an ‘oh’ under their breath while others rolled their eyes. However, the point this professor was making is that coral reefs are one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet and if there were to exist currently unknown compounds capable of revolutionizing medicine, we should start by looking in reefs.

Researchers around the world have seeking to gain a better understanding of the complex communities that make up coral reefs. This lends insight into how the reef functions as a whole and, also, what kinds of compounds are found there. As a fall intern at the Wrigley Marine Science Center, I had the opportunity to speak with Johanna Holm, a doctoral candidate in the department of Marine Environmental Biology at USC, about her research on soft corals, as she busily collected samples with a scalpel and tweezers before hopping on the ‘school boat’ back to the mainland.

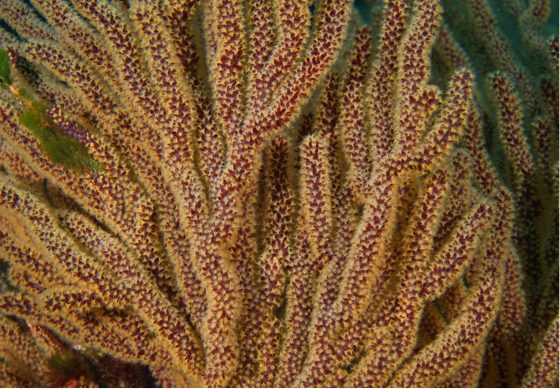

Brown (Muricea fruticosa) and Golden Gorgonians (Muricea californica), kept in large tanks near the Wrigley dock, are central to Johanna’s research. These brightly colored corals are among the organisms permanently attached to rocks and other objects on the bottom of the ocean. The tiny dots covering the surface of the coral are the white and gold polyps that enable both species of coral to filter feed. The corals’ fanned branches are home to arthropods and crustaceans, and provide food for some fish. Seeing these corals around in the water when snorkeling indicates that the bottom (benthic) ecosystem is diverse and, likely, thriving! However, also on the coral and invisible to the naked eye is a micro-society of bacteria, archaea, and protists, called a microbiome.

Johanna has been studying the different microbiomes found on the Brown and Golden gorgonians. Each gorgonian lives symbiotically with many organisms that comprise its microbiome, a relationship where all organisms benefit. Her research suggests that the coloring of the polyps is due to varying numbers of photosynthetically active cells. Johanna’s research shows that this and many other activities, change the surface of each coral species enough to attract different microorganisms – creating distinct microbiomes. Understanding these microbiomes is especially important to medical doctors and researchers looking for new compounds in marine organisms that can potentially be used to treat viruses and other diseases such as cancer, heart disease and asthma. The cells responsible for the photosynthesis might be a never-before identified microorganism or could be a component of the coral itself. The results and their applications remain to be seen!

Elise Steinberger is a fall intern at Wrigley Marine Science Center, learning more about marine science before beginning her Master’s in Health and Science Writing at Northwestern University.